Valérie Favre

Published: April, 2010, ZOO MAGAZINE #27

In her huge new studio in an old industrial complex outside the center of Berlin, the Swiss-born painter Valérie Favre is in her element. Several paintings are hanging or leaning against the wall and on a table lie two large ink drawings depicting a suicide.

Valérie Favre: I specialize in the suicide issue. I love to have the possibility to choose what I want to put attention into my art. In our Western-European society, which is based on Jewish-Christian thinking and moral tradition, we are not allowed to choose our end. This approach hasn’t been that obvious, however, in ancient Greece, where you could choose the moment in which you wanted to say farewell to life. It is still different in Japan.

Marta Gnyp: Are you taking on this issue for personal reasons or do you want to break a social taboo?

VF: It is more a geopolitical issue that I want to touch. I’m not depressive at all, although I would like to have the choice to decide on the moment of my death. What is important for me is to speak about this problem in our society as an artist and to make my reinterpretation of this subject.

MG: Do you think that our society could change if we could speak freely about death?

VF: I think so. Despite the fact that we learned to speak more freely about many subjects, like sexuality, death remains a taboo, perhaps one of the last. It is not the task of the artist to break all social taboos; in my opinion, the artist’s position is to warn about the complexity of some issues and to explore them. It must be unbearable for many old people who are ill, who enjoyed a good life but have no other choice than slow dying in sometimes humiliating conditions.

MG: It is striking that the opposition against the personal choice for death is so strong. There are so many people on earth at this moment that finally, we should be forced to think differently about the issues of birth and death.

VF: Exactly. You are not allowed to speak about the limits of life; on the contrary, the birth of a new life keeps its enormous high value. Several contemporary philosophers are already calling to reduce the population growth because finally, this growth is a real collective suicide. Our earth cannot handle it. The series I painted about the many ways to commit suicide is my small contribution to engage in this discussion.

MG: By painting about this subject you intend to provoke a discussion?

VF: Yes, it works. This series was, for example, presented in a museum in Lucerne in one separate room; it was amazing how many discussions it has provoked. Many visitors felt attacked. A painting as such is not aggressive but the reaction it triggers can be. This is what fascinates me in art; art is for me a basis for thinking, something that can help open our mind. Obviously, a painting is about materiality and sensuality; this medium is fantastic even if you would limit the experience of it to these visual and material qualities. My intention is to explore more.

MG: You want to offer to the viewer more than an aesthetic experience, confront him with some issues and let him think. This sounds like the avant-garde idea that art can change the society and make a difference.

VF: It is a bit romantic. I know that this idea is utopian and I realize that the utopia is not more possible in our time. I’m a person who has her feet firmly on the ground, hovering between the extremities of desperation and optimism. I would define myself as pragmatist with humor.

MG: If you change the attitude of only two people then that is worth doing.

VF: Yes. The same applies to my teaching at the Universität der Künste in Berlin. When I’m posing the question to my students: ‘what are you doing with your painting, what is your intention?’ I’m trying to make the students aware of their thoughts and actions. I’m not a dreamer but I believe that I can contribute to a change. In my opinion, good artists—I consider myself as a small good artist— should try to speak about complicated issues with the young generation. It doesn’t make sense to be egoistic either.

MG: The remarkable narrative way in which you paint touches the viewers. It makes possible to draw their attention to what you want to say. On the other hand, having a message is so passé in our time.

VF: Yes, you have to be very careful with the term message. I just want to confront the viewer with an image that would open new possibilities of thinking or seeing the reality.

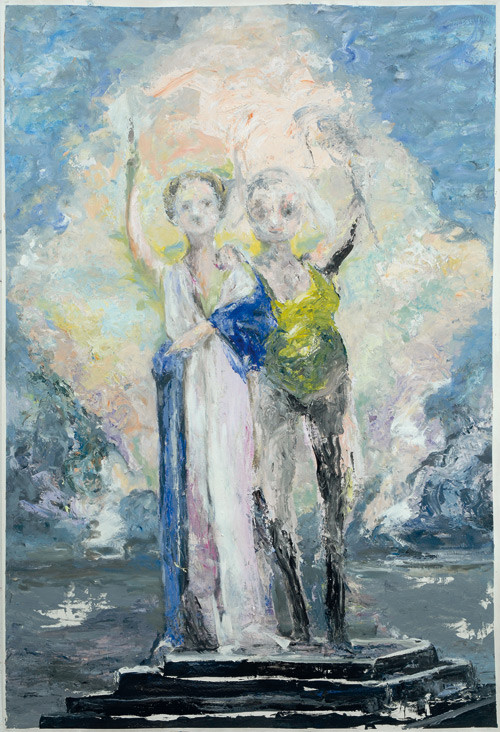

MG: I would like to talk to you now about paintings of famous artists from the past, which you sometimes reworked. I saw your painting based on Deposition from the Cross by Rembrandt, in which you replaced the biblical figures with rabbits, majorettes and other slightly ridiculous figures. What did you want to achieve with this action?

VF: I wanted to change the camera of this painting—the camera as the metaphor for a position in thinking. Women and mythological figures replaced the biblical figures. I wanted to let you think that if the women had more place in religion, history would be different. Maybe not better, but different. Most of the personages are majorettes, who are normally soldier women playing for men. It is a sarcastic way to express my fear that as women, we have little chance to open our mind, that we always play a game for men. Actually it is a very sad painting.

MG: Did you get a lot of critique for having misused such an icon of art history like Rembrandt?

VF: Of course! One museum refused even the painting for a show, because it was too complicated for them. Besides, they had to cope with my other subjects like cockroaches and suicide, so this would make the exhibition very sad for them.

MG: Were you not afraid of the critique that you are repeating the appropriation, a strategy that has been applied already many times?

VF: Not at all. This is a very contemporary strategy which works for many artists not only in painting but also in film, literature and music. A good appropriation becomes a parody and I’m a very good thief. I’m making an original painting but my idea belongs to everybody. The conceptual artist Joseph Kosuth said it already before I did. My art is, in this sense, conceptual as well. But I’m using all the materiality to make the object bizarre.

MG: Speaking about bizarre, let’s move to your subjects: cockroaches, cars, birdhouses are your favorites. Why cockroaches?

VF: During a period of time, I used to paint a lot of animals like horses and dogs in wide landscapes. All of a sudden, they became too pleasant. I wanted to paint a classical nude but the human body was not interesting for me; I wanted to make a reinterpretation of the nude and then suddenly the form of insects and the idea of butterfly crossed my mind. The butterfly is also a metaphor for the collector. I tried to paint a butterfly but it was too comfortable. The next step was the cockroach; the difference between a cockroach and a butterfly is misleading: the form of the body is similar although cockroaches are considered ugly. For me they represent human lowness and the wish to survive.

MG: Did you paint from a photo?

VF: I never paint from a photo or an image, only from my memory.

MG: Because you don’t want to block your fantasy?

VF: Exactly. Because the doubt about the image is the very essence of the painting. I need to put the picture in my way. We are living in a world where images and pictures dominate us more and more. As a painter, I have to destroy them to create a new one. It is about power. [Favre now shows us a sketch for a new triptych about the death of Seneca.]

MG: Why do you use the triptych form so often? It has religious connotations.

VF: It has nothing to do with religion. This form is a practical solution for the fact that I’m a woman and I can not move one big painting alone very easily.

MG: I see that you have painted many ghosts recently. Why?

VF: It is a comment on the possibility to show your work or not to show your work. Ghosts represent for me the idea of absence and immateriality, while the painting is the opposite, the pure materiality. The idea of ghost painting comes from Goya. I like to paint a lot of small ghosts.

MG: So now you are in the phase of suicide and ghosts; before there were rabbits…

VF: I invented the rabbit personage to play with the macho German painters when I come to Berlin. I like very much this macho culture. I’m not frustrated by them at all but I was just playing with them to say, “Hello, I’m still alive and happy even without a penis.” This is why I invented this wordplay—‘lapine’—the female rabbit, which is the French name for a penis: ‘la pine.’ To paint a rabbit is rather silly, but my rabbit is not a rabbit but a penis.

MG: It seems that you stopped with this series.

VF: Last year I painted only one.

MG: Does it mean that you don’t need her anymore?

VF: Yes, 10 years ago when I came to Berlin she was very useful for me.

MG: In one of the essays about you, I read that your first two years in Berlin were the years of silence.

VF: I have to think about the fragment of an essay by Walter Benjamin about walking as a stranger. It was a period of silence because I couldn’t speak German at that time, and felt sometimes as though in a cage, although I made many friends at that time. This was a period when many artists came to Berlin.

MG: Why did you come to Berlin?

VF: I used to live in France for 18 years. The painting as medium was completely dead and boring. I was ambitious as an artist and I felt unsatisfied because I wanted more. I went to Berlin for a show in 1996 and thought immediately that this is the place for me, away from Paris. My paintings at that time were more related to design and a bit sleek. I felt like I was standing before a big wall that I wanted to cross over and Berlin gave me the possibility to do it. Of course, I could consider going to New York, but I found Berlin much more destroyed and felt the possibilities.

MG: There are new artists coming to Berlin every day. Do you believe that there are special places in the history of art that trigger creativity, i.e. Florence in the early renaissance or Paris in the 1920s? Is Berlin from this point of view now the place to be?

VF: I guess so, because of the creativity of production and contacts between the artists. We are speaking about art and drinking beer together. Berlin is not as expensive as many other big cities. Many artists who use constructions in their work can produce here.

MG: Are there things about Berlin that you don’t like?

VF: Berlin has changed a lot during the last years. There are streets with shops like in all big cities in the world, which was not the case when I arrived here. This is a pity but the city is still very fascinating. Berlin could have more small, independent institutions for contemporary art. We have big museums and many galleries but not sufficient institutions suitable for experiments. A gallery is playing on a different level and in a different financial context, so we need both.

MG: Can you speak about German and French painting?

VF: I would think so, although the French contemporary painting doesn’t exist. Shortly speaking, the German painting is the consequence of the war, a dissident model that could go on from one generation into another. In France, we have had a competition with American artists who didn’t destroy the painting but launched the disastrous discussion about abstract and figurative painting, so the French fell in the trap. For sure, French artists presented new positions about painting like Buren or Toroni —the super-surface; they make everything empty, which is a very good position, but they made impossible to fill it again, which in Germany was still the case. Beuys declared that everybody is an artist, while Richter and Baselitz took a completely different position. In France, there was a complex problem about the artistic identity.

MG: Speaking of abstract painting, could you tell us something about your project Balls and Tunnels?

VF: I make one big abstract painting once a year until I die. This project began in 1995. Regarding the colors and composition, I’m playing with chance and coincidence.

MG: Do you sell those works or you keep them for yourself?

VF: I sell them but they are more complicated for the market because they are not immediately recognizable as my paintings. This is a problem for some buyers who like a clear artist’s handwriting.

MG: At this moment your works have been bought by several museums, you have many shows coming in the next months. Do you enjoy it?

VF: It is fascinating to look at your own work in bigger spaces. Mostly, you make several works for a gallery show, you come to the opening, a month later the works are gone. You come to the empty studio and you have to start again.

MG: Your work is also popular in France. Do you think that you will contribute to the recovery of painting there?

VF: Yes, my position, which I share with some other artists, is now considered as new painting school. Students at the academies are trying to show me their work. Still, I don’t regret my decision that I left Paris; it would be too stable for me.

MG: A form of suicide? I read that when you were in Paris, before you started to paint, you had a career as an actress.

VF: I had always wished to be a painter but I had no money. It was a difficult time to find a job and I had some personal problems to solve. In order to study painting, I needed to earn quick money. I used to live in Geneva, a very small and rich town with a big theater where I started to paint decors. One day, the theater director came along when I was working and saw me moving and acting as the dŽcor painter. He asked me to play in his play. It was an easy decision since I could earn much more money and my role was limited to walking but without saying one word. The critics were merciless about the piece except about one interesting, promising actress—ValŽrie Favre. Thanks to that article, I could go to Paris to work as actress.

MG: Why did you decide to stop playing?

VF: Because of the limited space. I’m not an actor: you have to speak out a text, be aware of the technical possibilities of the place, listen to the director who is giving you orders, react to the public. Once I saw Hanna Schygulla, who combined all those aspects completely effortlessly and naturally, and I realized that I would never be able to do this like her. For me, acting was a fantastic time to learn. I was lucky to cooperate with great actors and discover many possibilities. I decided though to be the director myself, to make the decors myself and to play myself through the painting. Sometimes I tell myself I’m a director.

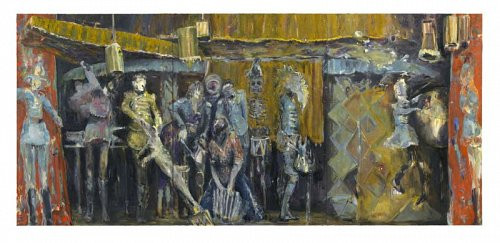

MG: Your paintings are very theatrical.

VF: Yes, through painting I’m rediscovering my life, although it is not autobiography. I try to start fresh with every painting and overcome new obstacles in my way. The everyday life of the painter is to go to the studio and paint as much as you can. At this moment, I’m working on big collages, which are very important for me; they are like a silent theater. They have the power of contemplation—completely different than the painting. The oil is taking so much energy that such contemplation is not possible: colors, the historical references of the canvas, make the paintings always a battle.

MG: Who are your heroes of art history?

VF: First, I would like to mention the writer and psychoanalyst Lou-Andreas Salomé who was a very close friend to Nietzsche, Paul Ree and Freud. She was my first big icon as a woman. Her independence in social conventions, her autonomy in thinking and behavior, helped me to try to be who I am. Regarding the painters I can mention, many male figures like Manet, Goya, Ensor and Munch, and the whole spectrum of modern and contemporary artists from Barnett Newman to Lucien Freud. Eva Hesse is for me the big woman artist. Gerhard Richter was also of great help for me to understand the possibility of sharing between the figurative and abstract art. He also combined the visually irresistible pictures with geopolitical issues.

MG: Geopolitical issues seem important to you.

VF: Baader-Meinhof (October 18, 1977), about the death of RAF members, was such a powerful series: it was painting from a different point of view. He opened my mind and changed my way of thinking about painting too. You can paint a lovely small room, a landscape or flowers, but you have a choice to think and work in other categories as well.