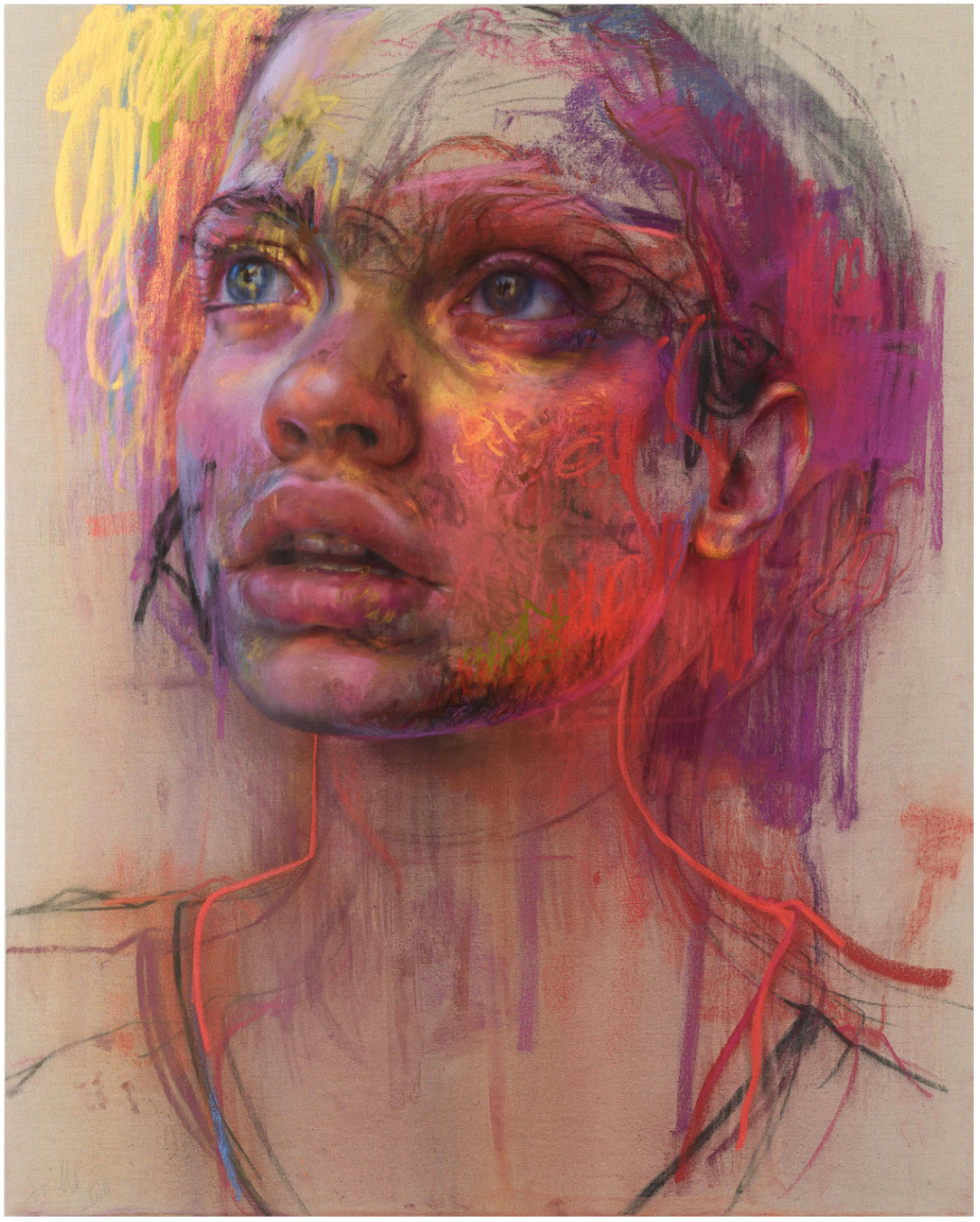

Jenny Saville

Published: January, 2024, Jenny Saville for the book "New Waves. Contemporary Art and the Issues Shaping Its Tomorrow."

Marta Gnyp: How have you been? Has the corona lockdown affected your practice?

Jenny Saville: Well, my daily life has not been that different. I’ve noticed that friends of mine have found the impact bigger. I stay in a studio all day long, I’ve got two kids, two studios and a house that are really close to each other. To encourage my kids to be compliant in lockdown, I’ve made a studio at home as well. The one difference I would say is I bought a truck.

MG: What for?

JS: I hired one at the beginning of the lockdown for a few weeks because I presumed that if I’m going to have this studio at home as well, then I’ll need to be able to move paintings and materials between all the spaces. When I finish a work or the painting’s wet, I can store it in the truck or I can move paintings myself to the studio and get more materials. So, I hired this truck and It’s been quite fun to have that actually! I can’t believe I hadn’t got one before. It was my fiftieth birthday in May – so I got a truck for my fiftieth birthday. The truck’s also become a cinema because we use it as a cinema screen for the street, so that’s quite cool.

MG: Happy belated birthday! So now you have four studios: the two previous ones, the studio at home and the truck.

JS: Exactly.

MG: Regarding your older studios I read that you have one studio for drawings and the other one for paintings. Does it mean that you have to decide every day before you leave your house what are you going to do?

JS: Well, it didn’t evolve quite like that. I had this amazing, large studio that I rented from Pembroke College, which is one of the colleges in Oxford where I live. The agreement I had with the college was that I could work in that building until they started a renovation project to expand their college, which involved knocking that studio down. When the project started, I had to move out, but they felt sorry for me and gave me a sort of fifties prefab office to work in. It’s probably physically the worst studio I’ve had in the last two decades, but I’ve made a lot of work in there. Then the college proposed to restore the prefab building as well, so I had to move out again. I found this wonderful painting studio to move into, however the college then decided not to do the restoration of this fifties prefab after all, so I kept it and ended up with two studios. It’s become more of a drawing studio and that’s helped my work.

MG: What do you mean by drawing?

JS: It’s an exploratory space. I use oil bars and all types of drawing materials and I paint in there too. I often start paintings there and then I move them to the painting studio. When I say painting studio, I do drawings in the painting studio as well.

MG: What makes it the painting studio then?

JS: The painting studio has skylights and a much bigger factory floor. The other one, the fifties prefab, is in the center of the town. Sometimes in the winter I work in one more than the other but it’s not really so separated.

MG: Quite a luxury to have so many possibilities.

JS: Yeah, I must admit it’s a luxury that I didn’t design, it just arrived, and I managed to hold onto it.

MG: Why do you need so much space?

JS: I tend to get a studio and fill it with work. I only sell a tiny fraction of what I make. My drawing studio has got thousands of things in it and I only put together shows of certain things. I see it as a very explorative universe, like a child’s bedroom, just on a bigger scale.

MG: Your gallery shows are rare. I always thought you make few works, now I understand that you simply don’t want to release them.

JS: I have many works in the air, but I probably only push certain works to the end. At the beginning I made less work, now I create more and the works are more open. There might be several paintings around the one piece that actually leaves the studio.

MG: What do you do with the other works left? Do you continue working with them after a while or you just throw them away?

JS: Oh, it’s both. They just kind of kick around a bit. I’ve learned that you can get quite dogmatic and use old tricks to get paintings finished. That’s very annoying because they can become illustrative. I learned that staying back from them and keeping them open is helpful for the development of the work. It’s about how I can build a language for myself and the development of what I want to do.

MG: How does this building your language work in daily life?

JS: I have these bits that I don’t really see as painting. Sometimes I might see a painting on the floor that is totally abstract, and I just leave it like that because there’s something in it that’s interesting, and I push another one. When the other one is getting too tight, having the very open abstract one around in the studio helps me think differently.

MG: Have you also kept many works from the past?

JS: Oh yeah, things are just kicking around you, they pile up, so I just stack them up in the storage facility. I have all sorts of things; drawings, bits of drawings, paint studies, newspaper with paint on them. I’ve got hundreds and hundreds of photographs of different things, medicalpictures, images of graffiti and art history. I photograph my palette because it’s got color combinations on it that I just can’t seem to articulate on the canvas, but they’re more interesting on a palette. I would photograph that or do a print of that on another piece of paper and I keep those. It’s like having a vocabulary. If you’re a writer and you read a piece of poetry with a line that is poignant, you would stick it up. I pin up those things in my studio in the same way, and they prompt me to go in one direction or another.

MG: You expose yourself permanently to explosions of images.

JS: I’ve got lots of images of war zones – I don’t paint anything to do with that directly, but they give off a sensation I’m interested in. I have art history images on the floor; for example, Pablo Picasso images. When I wander around, I’m able to unlock those images. I see bits of a Francis Bacon’s painting and start to work out, why does that work?Why is that so good? I’m not sitting at a desk studying it, but because it’s there and I just pass by, it becomes part of my language. I’ve just developed that over the years. As I’ve gone on, I’ve realized how important that is.

MG: You observe and absorb all the time.

JS: To see the way a drip has gone on a pavement is literally as useful to me in the body of a work as looking at a medieval altarpiece. I don’t follow the hierarchy of art history. Recently I’ve been collecting images of those heat sensations made with thermal cameras when they’re taking temperatures of people with Covid-19. I have no idea whether that will enter a painting. It could just as well be a color combination in pastels that I use. I work very directly, building those sensations up.

MG: Any favorite subjects?

JS: it can be literally anything, it’s about the nature of things. I love flying and photographing the horizon line and the way it changes, or sunsets or autumn when you see the most vivid red leaves on trees next to blue skies. I’ll stop my bicycle on the way to the studio and just photograph that to hold it. The act of photographing is a sort of conscious putting it in your memory. I don’t always look back at the photographs; it’s just a way of stopping and acknowledging that that’s gone into my visual memory.

MG: Do you always paint from photographs?

JS: That’s the basis of how I work. I don’t like to have live models in the studio.

MG: Why not?

JS: Well, it started a long time ago. One, I wanted to work on a larger scale, and to scale up when somebody is in front of you is more difficult. If I have to articulate a painting when the models are in front of me then I don’t have enough time to think about how I make that image, the possibilities of the paint. Also, I’m not only painting that specific person. I’m much more related to the way Francis Bacon worked in the sense that there are lots of realities going on and I sort of rebuild them in the painting. I’m not a portrait painter in the traditional sense.

MG: You also play with abstraction in your work.

JS: I look de Kooning and Pollock a lot; I was lucky enough to spend a day in de Kooning’s studio when I was in my early twenties. I was at the house of my dealer Larry [Gagosian] when he said let’s go there. De Kooning had just died a few years before, Lisa de Kooning was living in his studio house. I went over there, I was just given the keys to the studio and got to spend the day there.

MG: Did you discover anything precious for yourself?

JS: I probably learned more in that day than going into art school in its totality. It was the atmosphere and the practicality of the way he worked. Since this visit, I work with two long, glass palettes. He guided me in studio techniques; the way he mixed up in bowls, kept color mixing charts and painted with floppy, house-hold brushes. I was able to short circuit years of development by being in his studio that day. I saw the potential of splitting up my process into small elements, like mixing my tones in pots. I spend all day mixing paint tones, so I know that when I’m in the act of painting and putting paint on the canvas those tones will do a certain job. I got to think about painting in the same way that a musician thinks about composing layering sounds, how I play those sounds; I learned that from being in his studio. Coming back to the previous question, If I had a model in front of me, I just would not have the time to break up that process.

MG: You mentioned upscaling the size already; you seem to prefer making large paintings.

JS: That’s a bit of a myth about my work. I make small paintings too.

MG: You don’t release that many of them.

JS: Sometimes I do, but they tend to be the ones that just kick around my studio. Because I showed at the Saatchi Gallery when I was younger and it was such a vast space, I think this set my mentality about showing big works in big spaces. I also wanted to be taken seriously as a figurative painter. At that time, if you made small figurative paintings, there was an academicism attached to it of making things that were kind of comfortable for a living room. I was working against that. I think it set my mentality in a certain way; if I did a show and it was a big show downtown in New York, I wanted the work to have a monumentality.

MG: Do you still believe that?

JS: It’s taken quite a few years to unravel that, actually.

MG: Your early works such as Propped or Branded, which were made during your study, were large already.

JS: I’ve always had a natural instinct for scale. I get shocked when I see a photograph of myself in front of a painting. I get shocked that the paintings are so big in relationship to people’s bodies.

MG: How come you associated large painting with serious art?

JS: I wanted to make work that was like Rothko, de Kooning or Pollock. When I was at university in Cincinnati for a period, I visited New York and saw those big-scale paintings. I’d also grown up being in Venice looking at Titian’s altarpieces and those large Tintoretto works. I thought serious art is made on a large scale and I wanted my art to be taken seriously.

MG: Which worked! Let’s go back to the very beginning, the period of Young British Artists. You studied at the Glasgow School of Art between 1988–92, which means you were a bit younger than the core group of the Goldsmith YBA and were not a part of the Freeze exhibition. Was the show the talk of the town or talk of the country? Did you try to be part of it?

JS: Glasgow was much more traditional; it was Kiefer and Baselitz everyone was talking about. There were so many stories about Kiefer putting airplane wings on the side of the paintings and grand Baselitz dinner parties. I didn’t know about Freeze or what Damien [Hirst] was doing at that time. It started to creep in with art magazines I read in the art school library and people started to talk about that. I’d hear about shows in New York; things like that. I became interested in the Saatchi collection, so that would be the place to visit if you went to London, alongside d’Offay and Marlborough galleries. But the painting tutors in my department would scoff at that kind of work. Anything in the New British Art show was dismissed even if students were starting to take notice.

MG: Where did you get the ideas for your paintings?

JS: I wouldn’t have made them had I not been in Cincinnati.

MG: Which was a half year exchange program at the university there.

JS: When I went to university in Cincinnati, I was lucky enough to find a famous department of gender and sexuality studies. I didn’t know it was a groundbreaking department, I just drifted into going to some talks there. I was trained by my uncle in very academic terms of making paintings: paintings by Rembrandt or Titian, old master paintings, genre paintings. Then, in Cincinnati I started reading about feminism and women’s studies and it sort of blew my mind. When I started looking at women artists that were working around the subject of feminism, none of them were painters that I could connect with. I started looking at Cindy Sherman and Jenny Holzer, but I couldn’t really reconcile myself as a painter with that thought process. At the beginning with Propped, I was trying to articulate what I couldn’t do; that’s why I used the texts from Luce Irigaray across the image. I was trying to navigate how to paint the woman and became interested in the group of writers attempting write the woman with the écriture feminine.

MG: You wanted to find a new way to paint the woman.

JS: I had this very traditional training; I liked Bacon, Velázquez, Degas, and all that tradition of painting. But I had more forward-looking and progressive thoughts about women’s studies and feminism. My work was about reconciling those two things together; how to articulate the painting of a body with those things in mind.

MG: Those paintings were interpreted also as breaking taboo about the ideals of female body.

JS: I don’t know whether I was successful with that; at the time I just couldn’t give up painting. I tried making photographs, I tried doing installations, I did cast of bodies in plaster; I had all these casts of corsets. I did a lot of other work around and about the subjects, but I felt a deep sense of homesickness about painting, so I knew that I had to paint.

MG: Painting itself was almost like a taboo.

JS: I literally think in paint and I think through paint. Everything I see, whether it’s that stain on the pavement or graffiti, is thinking through, how can I use that in a painting? How can I articulate that? My life’s work has been articulating that.

MG: I know this is not such an interesting discussion, but almost every generation dreams about the death of painting, in vain. The profound hatred towards the painting is just very strange and persistent.

JS: I found a quote from ancient Greece that mentioned a debate about whether painting was still alive and thought, wow, this is so timeless. Have we had the same debates about sculpture, why is painting this big enemy? I can understand it from a feminist perspective because it’s such a central canon in Western (male dominated) art. Because of that, it’s very hard to find a space to move within it.

MG: Some rediscovered female artists are coming into the fore like Joan Semmel, who had in the 1970s similar problems as you had in the ’90s. There weren’t really role models for nudes painted by women.

JS: There was a group called Women in Profile in Glasgow and I used to go to some of their meetings. When I put my degree show up, I experienced hostility from some of the members because it was a naked female body that was being shown. On the other side, I would have the more traditional people interested in art who would say, “Oh my God, why have you destroyed your painting by writing texts across it? What the hell does that mean? You’re quite a good painter. What are you doing destroying your work?”

MG: Could you cope with this criticism?

JS: I read enough about people like de Kooning: when he first did Woman One, he was attacked by all sides, partly because it wasn’t properly a figure and it wasn’t properly an abstract painting. I knew that if you exist on the border of things and annoy different camps, you’re probably doing something interesting.

MG: What about the exhibition Sensation? if you speak with collectors even today, many of them will say that it was the most defining show of contemporary art that happened during the last forty years. Did you have the idea that you were participating in something extraordinary?

JS: Sensation started in London in 1997 at the Royal Academy in London and was showed in Brooklyn in New York in 1999. By that time many of the artists experienced it as a retrospective view actually because much of the art had been shown quite a few years before. Damien’s [Hirst] Mother and Child (Divided), Jake and Dinos Chapman’s work – we’d all seen these shows and knew that Charles [Saatchi] was collecting the work. For the artists, the previous Young British Artists’ series of exhibitions that the Saatchi Gallery showed in Boundary Road were much more important. They were key because much of the art was commissioned by Charles directly, shown there for the first time.

MG: You showed your work there in 1994 as a very young artist. How was it for you?

JS: it was a shock to be given such an amazing space to show. I don’t think I’ve ever shown in such a beautiful space as Boundary Road in London. This enormous platform that Saatchi gave artists had no precedent at all. The artists that showed there before were Richard Serra, Cy Twombly; one of the galleries was called the Twombly Gallery in London – and Charles was giving over this space to 25-year-olds to do whatever they wanted! It was an incredible act of faith at that time. Obviously, Charles has a reputation about playing the market and being a dealer, collector, all those different things. I was twenty-one; he flew me to London and said, “You can make whatever you want in this space.”

MG: Amazing.

JS: He gave me some money so that I didn’t have to have a job as a waitress anymore. I spent a couple of years inside a studio, not going out. I didn’t speak to anybody about it, I just got my head down and made paintings. Charles did the same with Damien and Sarah Lucas too. He showed a lot of women artists at that time, which is something that’s often forgotten. There were not a lot of galleries showing women artists. People always talk about Sensation, but actually those Young British Artists shows had a phenomenal amount of people coming to the openings, all talking about ideas, from musicians to writers and poets. It was really exciting.

MG: Do you still have contact with Charles Saatchi?

JS: I don’t anymore, I used to. There was a fun period when I first started working with Larry [Gagosian] and I’d have dinner with both of them. We had a lot of fun evenings chatting about things, but I’ve lost touch with Charles. I didn’t really like the space when they moved to County Hall and I just wanted to show paintings in New York.

MG: Going back to the Young British Artists for a moment, what do you think is their legacy?

JS: It created an incredible journey in the UK for creative platforms. It wasn’t just art, it was music, it was design studios, London became culturally exciting. It was possible to have a career or spend life making art, whatever background you came from. A whole community of artists were able to exhibit in London and started showing internationally. In 1999 my first Gagosian show opened, it happened the night after "Sensation" opened at the Brooklyn Museum. Everybody was in New York and there was a feeling that we’ve become international artists. It was exciting to think of all the artists we were looking at when we were younger. Those Charles was showing – like Serra, Twombly, Brice Marden, Robert Ryman. We were becoming part of that conversation.

MG: It’s amazing how quickly you joined that conversation.

JS: Charles Saatchi’s daring vision also encouraged a lot of collectors as well. When I talk to collectors in their mid-fifties, late forties, they always say that they went to Sensation, that they saw that, started making some money and wanted to collect too.

MG: In "Sensation" you showed Propped and Branded, large paintings of female nudes or more exactly a lot of flesh, which has become your trademark if I may say so. Where is your fascination with flesh coming from? You paint female nudes but very fleshy ones, you hardly paint skinny persons.

JS: I paint all types of bodies. From a young age, I’ve had a fascination with painting flesh. I loved Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud and Frank Auerbach and Titian and Velázquez. I was fed Rembrandt from my uncle who was an art historian and an art teacher. I grew up with the idea of paint having a physical substance and I still think of paint like that.

MG: You also studied flesh in a plastic surgery clinic in the US. Were you driven to understand how the human body works or were you more interested in the many appearance of human flesh?

JS: One of the collectors who was hosting me in Connecticut introduced me to her surgeon in New York. I was interested in cosmetic surgery I’d made a painting called Plan and quite a few works around the idea of surgery. Body modification was in the air. It was in fashion magazines, I was reading about it and saw target marks on a stomach in Cosmopolitan magazine and thought that they looked like contour marks on a map. I learned about liposuction, which was a technical termat that time, not a mainstream language. Going to New York, I had the opportunity to spend time at a medical library on 102nd Street, which has a large section on plastic and cosmetic surgery. I would go there for research and I’d go in the surgery and see operations. My interest moved from regular cosmetic surgery towards plastic surgery and what flesh can do. I would see the transfer of flesh when you’re rebuilding a hand, for example, after an accident. This idea of moving flesh around and grafting flesh onto different parts of the body to change it became a model of a way to paint actually.

MG: What do you mean by the model to paint?

JS: Everything I see is a potential painting. When I see a surgeon’s hand pulling up the flesh on the side of a face and their hand’s going in and exposing layers, I start to think about the anatomy of a painting, what I can do in paint. From seeing the anatomy of a body, I take that kind of scientific model and imagine how to construct a painting with that in mind. I’ve noticed doing that quite a few times in my life; I’ve used methods from science, or music especially and applied them to painting.

MG: The painted flesh can be so fascinating. Paintings like Fulcrum or like Shift can swallow you.

JS: At that time, I was obsessed with creating a curtain of flesh or a landscape of flesh, and partly because I didn’t want the body to end.

MG: How can you paint an endless body?

JS: I loved abstract paintings all-overness. When you stand in front of Pollock’s Autumn Rhythm, it’s so all-encompassing, there’s no central point. I wanted that poetic movement in a figurative painting too. Or when you go and see Easter Monday by de Kooning at The Met, and think, “How can figurative painting be like that with no ending?” So, the whole painting was flesh, and that was my way of articulating that.

MG: You already mentioned that you faced critical comments about the way you painted the body, especially female bodies. In the beginning, you were overtly using the feminist theory, what about now? How is your relationship with criticism and with feminism?

JS: At the beginning I was almost apologetic that I liked painting. Because the things I read were against that canon of painting. I felt guilty that I loved painting so much, and it took a few years to throw that off. But now I feel that I took the right road, it was actually my only road, even though it wasn’t the established road as a feminist, to articulate my relationship with art history and learning that that’s my history too.

MG: You mean that you had to accept yourself as a painter within the narrative of the grand tradition of European painting.

JS: When I got involved with feminist studies, I started to think that art history is not mine, I was trespassing, so I felt I wasn’t legitimate in a certain sense. I had to build that legitimacy. Fundamentally that was good, because it helped me to think differently and understand the visual systems at play. Now I realize art history is my history and have every right to that history. That would probably be the only change in my attitude. I’m so busy working; I don’t even read reviews of my shows if I’m really honest, I just don’t. It’s so bloody hard to make a decent work of art, to really push it so that each time you’re working, you’re improving. I feel like I’ve got very little to do with the art world, if I can say that. I go to BaseI now and then, I love going to the Venice Biennale and see some exhibitions. But on a day-to-day basis, I’m just involved in trying to push the work as much as I can in the life I’ve got.

MG: I read that you are giving yourself an improvement report. I found it very interesting.

JS: I do that. [laughs]

MG: Sounds like a brilliant idea. Does it refer only to your painting or is it also about you as a person? Do you do it every day? I am really very curious. I think I’m going to do myself as well.

JS: Each painting I make has a clipboard where I write what I want to do to the painting. When I’ve got so much art in different studios, and lots of different paintings on the go at the same time, I forget what I was going to do on previous works. So, I sit and write down a plan: I do a lot of stenciling and dripping paint on the floor and then drawing again; things like that.

MG: Kind of instructions for yourself.

JS: I often write the sequencing down when I’m in the process of making a painting. Then when I swap onto something else, I can forget the details. When I want to re-engage with the painting, I look at the clipboard list and it helps re-open the painting. I also take photographs on my iPad when I’m working. Once when I finished a painting, I was looking back at iPad photographs and realized the painting didn’t develop in the best way, I took an easy route, or saw possibilities too late. I started to write that down and asked myself why did I take that easier road? What was wrong with my personality not to be brave enough to do that? I started to analyze myself and that’s where the report writing came. What went well, why did I get stuck and how could I re-approach that issue next time? It’s useful for growth. Sometimes you can get very dogmatic in paintings. Sometimes the ones with the big struggle can be the better works or they can be the worst works; it’s a constant game of negotiating.

MG: It’s not easy to be a good artist.

JS: To be a really good artist, you have to have a set of tools; a certain amount of patience and risk-taking and you have to harness the self-destruction that’s within you in the best way. So before, when I was in London making paintings like Fulcrum, I would throw paintbrushes across the room because I couldn’t get the painting to do what I wanted to. I just didn’t have the abilities at that time to create the painting that was in my head. So, you get stroppy, throw cups; you do all that stuff. In the last few years I’ve been able to use that self-destruction to push the painting more effectively.

MG: You changed it into your advantage.

JS: That comes from years of saying, right, “I’m really bored of destroying my work now or trying to perfect it. How can I use this constructive/ destructive life-force?” Young kids use that interchangeable life-force with freedom when they paint so I’ve learnt a lot watching them. It’s a bit like being an athlete where you train to a certain point and know you’re confident enough to rebuild. And when you rebuild, you get to a much better place in the painting because you’re working within the nature of the painting. The painting itself has a nature. If you’re only going along a very safe road, you never get to that. If I’ve improved, it’s being able to try and harness all the different aspects of my personality.

MG: Do you like to show this personal struggle? Are the paintings that you release for the big audience during your exhibitions the perfect paintings, the paintings in which you succeeded to achieve what you want?

JS: No, they are the paintings that work in dialogue with each other best. When I did Ancestors, my last big show in New York, I had notions of making the three Fates. I had three or four different approaches. The paintings that I showed where the best-articulated versions.

MG: Speaking about this show – you said you don’t care about the reviews, but one question about that specific situation: there was one review written by Roberta Smith, who is considered one of the most important art critics, that was quite negative about your show. She accused you of banality and sensationalism. Then three months later, your Propped painting sold for US$12 million that made you the most expensive living woman artist. What does it say? There seems to be disbalance between the critical judgment and the market, which is often the barometer of the taste of the time. This is not your subject, but do you notice this disparity?

JS: I didn’t really take any notice of that. I’ve learned not to do that. If I do that, it has a negative impact on my work. When something happens that’s a high price in the art market, in the auctions, I get texts and phone calls telling me what a great artist I am at that time. They’ll say, “Oh, I knew it was a masterpiece.” You get a lot of that for a few days after that, and people want to do projects with you. I’m used to the wave of that. And it goes in the reverse way: if the price goes low people question you and your career.

MG: Are you really so resistant to the public opinion?

JS: Either way it does not make me paint any better. I can’t take any notice of that. It just doesn’t have that much of an impact. I know that this is quite unconvincing to hear.

MG: It must have been quite exciting to your ego have this record for your painting.

JS: What’s good in general about the price of that painting Propped is that maybe it’s good for women artists in general to have that price raise. There were no women artists when I was younger with the price range like Cecily’s [Brown] for example; it’s a new generation of artists. When the majority of collectors with a lot of money are male, they would collect the work that represents their value system.

MG: Now the situation is changing, not only are there more women collectors, the male collectors have massively accepted women painters.

JS: That’s certainly true and it would be great to see more women collectors and a widening of the value systems that are considered interesting subjects for art. As that happens, I think that the prices of women’s work will rise or there’ll be more comparison between men and women in the market.

MG: I think it’s also great that this most expensive painting is about distorted nude female body painted by a woman, a kind of art historically reclaimed by a woman. By the way, do you think it makes sense to distinguish between male and female artists?

JS: Oh, I just wish they didn’t. One thing that I don’t like about what’s happening in auctions is they’re making genres of artists; the black artist is a market genre and the female artist is another market genre. That’s a worrying development. It’s used as a tool to sell, but in the longer term, it just means that the main canon remains white male, plus these other canons. As a collector, if you fancy to expanding your repertoire there are these other types of canons. I’m hoping these categorizations will fall away soon and merge together.

MG: That’s a very worrying development also in institutions. At this moment identity politics has become so important. There’s a big push in the institutional world and in art criticism as well to favor artists of color and female above male artists. That’s good, but I think what is annoying is that categorization is now so prominent, the quality of art has become of secondary importance and art is used as a political statement.

JS: You could have an argument against that because the value system of what you think is good-quality art changes with the amount of exposure that art gets. You can say, the quality is there for the art of de Kooning and Pollock because they were continuously exposed, so their value got expressed in big prices. But a lot of other art doesn’t get that level of exposure, you don’t see it constantly. If you take an artist like Jean-Michel Basquiat, now the market darling, he was not bought by MoMA in his lifetime; there was a lot of snobbishness against him. I look at his work a lot; I really love him as an artist. If you look at his drawings, this is someone who had an incredibly original language that he just kept pushing. I think that we might change our views about a lot of art that we consider not to be of interest, if it’s exposed enough.

MG: Sure. I read a lot of interviews with you recently, and one word that you are using very frequently is “freedom.” You mentioned that Twombly gave you freedom of thinking as artist. You also mentioned that your children gave you freedom. Is freedom the essential value for you?

JS: It must be; if I keep saying it; I’d never actually realized that. Around the time I had my kids, a lot of the outer world that I was interacting with saw having children as a restriction on my life and my inner world. I used to think the same as them. Actually, the opposite was true, the experience gave me freedom, so that’s probably why I’ve emphasized that. When I watched my children growing, their bodies changing, being pregnant, having another baby, the whole visceral experience of that journey, it made me want to make art. I experienced this life force for making art more than I had before. That was contradictory to what people were saying to me, “Oh, can you have a career? You’ve had all these babies. Can you actually still be creative as a mother?” Ironically there’s a lot of negative myth-making around motherhood and creativity. There was a moment where I’d started making these drawings and layering them up, me pregnant with my daughter and my young son moving around all the time. It was so exciting making the drawings. I then asked myself, “Are you actually going to show that work?” Because that really stamps you publicly as a mother and that’s a very powerful social thing to be.

MG: Were you afraid to be categorized as “mother”?

JS: I’d built up my career as an artist and had been taken seriously; I was dealing with these grand subjects of Western art history. Could I also say, I’m a mother too? Was that a challenge to the perception of my work? It was big decision to actually make a whole body of work about this subject and put it out there in a show called Continuum in New York. It was a good decision to make Continuum because it made me feel brave about showing everything that I am as a human being.

MG: For this show you used as a reference the famous Da Vinci’s painting with Virgin Mary and Anna. This was also extremely brave: you have taken one of the heaviest icons of art history, and you used it for yourself being a mother with your children.

JS: When you say freedom, I’ve tried to sustain that position in my work. I think that’s also why I haven’t lived in an art center. I work in Oxford now; that’s a slight distance. I learned that from talking to Twombly when I was quite young; having that slight distance keeps the freedom in tack. Because you have a playfulness that’s nothing to do with career, nothing to do with your position in the art world; it is literally you with materials in a room.

MG: You don’t have a lot of contact with other artists except when you are coming to your or others’ opening?

JS: I know musicians, poets, scientists, mathematicians in Oxford. It’s an international city with people all working in research one way or another. I feel part of that community and like the atmosphere of research, pushing the boundaries in science for example.

MG: I don’t want to take more of your time. You have probably a very busy schedule today.

JS: It’s really great light at the moment out of my window, I want to go and make some colors.