Is the Art Market Structure Today Still A Rusty Relic of the 19th century? – A Question to Marta Gnyp

Published: May, 2018, COBO SOCIAL

CoBo : Is the art market structure today still a rusty relic of the 19th century?

Marta Gnyp answers:

If you thought that the Internet and new media had completely revolutionised our lives, you would be surprised about how stable, or perhaps even old-fashioned, the structure of the art market is. The current system originated more or less in 19th-century France when the new capitalistic economic model allowed artists to experiment freely with artistic issues and subjects that were no longer dictated by the kings, the church or aristocrats. As a result, the artists got their long-desired, unlimited freedom to create whatever they pleased. But at the same time, they also had the heavy burden of searching for a public and buyers themselves. In this dramatic struggle for survival, they got support from the actors who had never left them: art critics and art dealers.

The Frenchmen Paul Durand-Ruel (1831-1922), Ambroise Vollard (1866-1939) and Paris-based Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler (1884-1979) are considered to be the founding fathers of the professional dealer. Their practice helped to formulate the unwritten rules of the profession, although its structure did take over some elements of the old system of patronage. By neglecting the dominant academic taste they managed to spot new key artists, acknowledge their importance and convince collectors of their outstanding quality. Interestingly, it was the dealers who recognised the relevance of artists, such as Claude Monet, Paul Cezanne and Vincent van Gogh in the first place, before the academic world or museums did. It is crucial for an understanding of the art world to know that those dealers didn’t have any art history education, but claimed to have followed their intuition or instinct; characteristics that have been celebrated among dealers ever since. They acquired their artistic knowledge by learning on the job, and it is often the same today. According to recent research, many dealers today have a high degree of education, but not in art history, and consider themselves to be self-taught in the field of art.

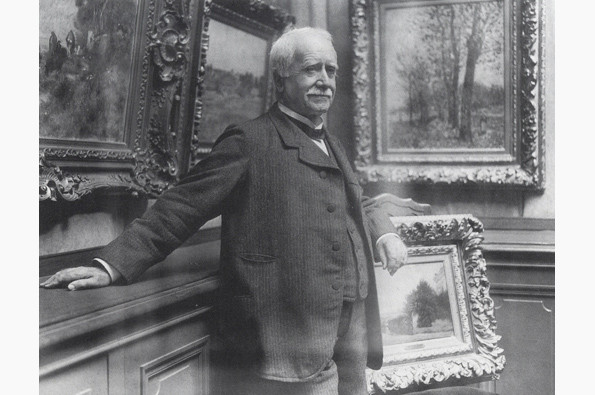

Durand-Ruel who operated from Paris, London and later New York, was one of the first to recognise the artistic potential and great value of Impressionism. Despite his conservative social attitude – he was said to be a loyal monarchist and ardent catholic – he fell in love with Monet, Pissarro and Renoir, and by using different market tools, managed to successfully develop their market. Being a part of the bourgeois circle might have even added to his success. So how did Durand-Ruel modify the traditional art market? He quit dealing in antiques and luxury objects – it was standard at the time to deal in these items in combination with paintings – and instead dealt only in paintings and prints. He also set up a journal to promote and explain the modern approach and embraced exhibitions of artists’ works, which has become the most obvious way to show art today. These exhibitions paid off only later on. At the beginning, Ruel complained they were good for artists, whose reputations they established, but were no good for sales.

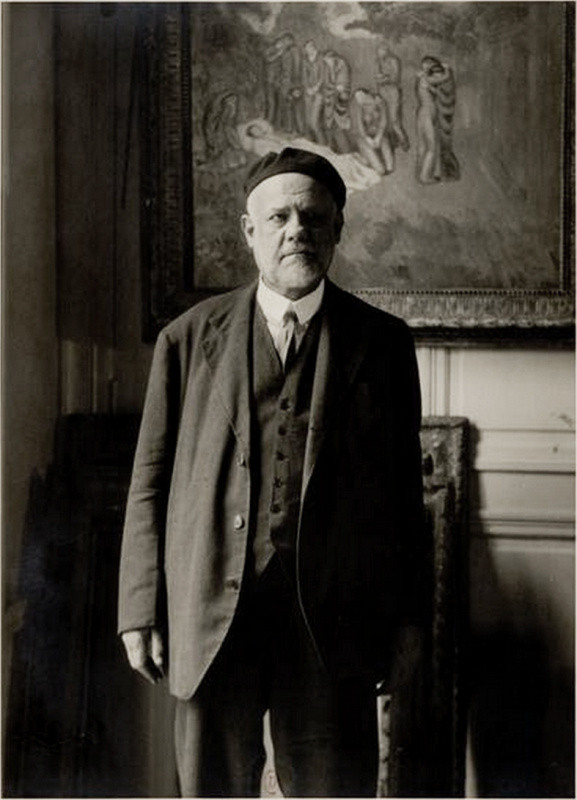

Another new aspect of the professional dealer’s work was the financial support they gave to the represented artists. They would often buy works in bulk, hold them for a long time and then actively create the artist’s careers, sometimes by taking big financial risks. Vollard began representing Cezanne after buying several of his works during a small auction; a purchase that apparently caused the dealer financial difficulties as he exceeded his budget and credit limits. Vollard was not afraid of buying difficult paintings (he gave the first show to the young Picasso and then later, the first show to Matisse). Although he was known as grumpy, he was held up to be a genius at selling. His own God was Cezanne, whom the dealer adored artistically and built up financially. In the long run, Cezanne created his fortune and Vollard apparently said: “I got rich in my sleep.”

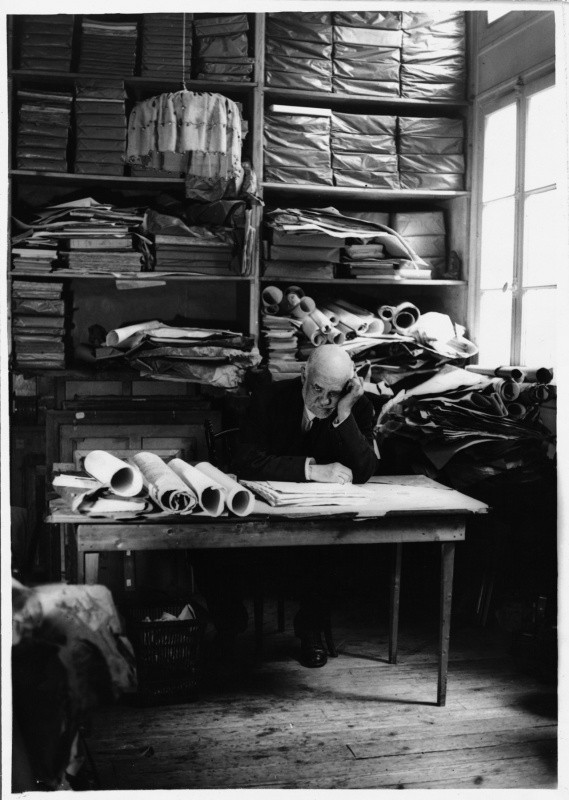

Kahnweiler was known as the big fighter for his recognition of Cubism as an artistic movement and for being an early supporter of Pablo Picasso and George Braque, among others. Serious, intellectual and disciplined, Kahnweiler introduced exclusive contracts for artists based on fixed prices for their works. Once an artist worked solely with him, he would buy many works at once so as to let the artist create without the worry of any financial concerns. His gallery was a forum for artists to show their works, but also to experiment. For example, he organised joint projects with writers. Kahnweiler created a gallery space with a clear identity that related to the cubist aesthetics, which at that time was quite unusual since the presentation of the works for sale normally took place in a rich ambiance. Picasso acknowledged his role in constructing artistic careers by saying: “What would have become of us if Kahnweiler hadn’t had a business sense?”

So, these three men helped to create the profile of the dealer: a person who represents the artist by supporting him financially, opts for a long-term strategy, rather than quick success, and takes care of the presentation of the artist’s works, both locally and internationally. They were not always right: all three also worked with artists who have now been completely forgotten. This shows that, to a large extent, the art market has always been unpredictable. Thanks to their work, the dealer has become the mediator between the artist and the public, although originally it was more of a select group than a big audience. The dealer-mediator has become one of the most important players in the art market. Together with the art critic, they have formed the system in which the artist can be discovered, recognised and marketed. Although a lot has changed, the artist-dealer-critic alliance still forms a solid foundation for the marketing of artworks today. This alliance creates an artistic value, while the physical exhibition space remains the fundamental place for engagement with artworks, despite the overwhelming virtual possibilities that now exist.