From here no longer to eternity

Published: October, 2014, DIE WELT AM SONNTAG (TRANSLATION FROM GERMAN)

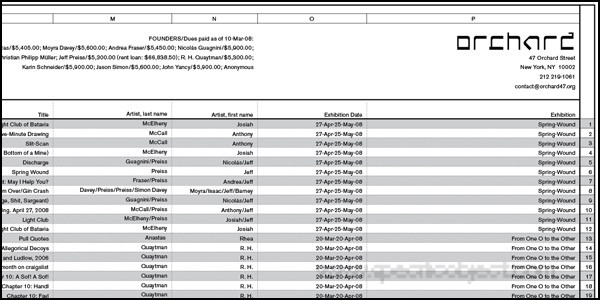

In 2009, the American artist R.H. Quaytman created her large, beautifully designed graphic print, Orchard Spreadsheet. The work is based on a financial spreadsheet that lists the artworks sold in the legendary Orchard Gallery in New York from 2005 to 2008, both by name and buyer. By making the buyer and cost publicly known, Quaytman, then director of the gallery, behaved rather peculiarly, as discretion towards collectors had always been one of the traditional rules governing the art world.

Why did she do it then? Perhaps to show that each gallery is not only creating culture, but also, selling art works, although the last aspect is never put in the spotlight. As the Orchard Gallery explored the social and economic conditions of artistic production, a work that demonstrates artists’ dependency on buyers in order to be able to produce art at all, makes sense. Orchard Spreadsheet also showed that the boom in the art market, which seemed to fuel the New York art scene at that time, wasn’t universally applicable, as differences between artists’ earnings were huge, while in the end the gallery was hardly able to cover their costs. In this work reality suppresses myth, which connects R.H. Quaytman to someone who would at first sight seem like her opposite: Stefan Simchowitz.

The South-African born, Los Angeles-based, self-proclaimed cultural entrepreneur, Simchowitz (born 1970) has become the enfant terrible, or, more prosaically, a pain in the neck for many galleries and art institutions. He was once a successful Hollywood film producer and owner the photo-licensing company MediaVast that he sold for 200 million USD in 2007, which paved the way for him to become involved in art full-time: as collector, advisor and dealer. Please notice, art wasn’t a casual impulse or a fancy he’d never thought of before; his mother is an artist and his father has built up a distinguished art collection of modern art.

Simchowitz started by promoting and showing art works through social media. Nowadays he discovers young artists by buying works in bulk against very low prices, helps them with daily problems and sometimes tells them what to do artistically. Simultaneously Simchowitz advises collectors what to buy, many of whom, follow him blindly, occasionally without even checking what an artist does. His Instagram account is full of pictures of artists, artworks, and people from the art world and sometimes of the eccentric Simchowitz himself embracing his little son, or holding an artwork with the text PRICK! Like a successful Hollywood film producer, the extravagant Simchowitz seems to aim at being as inventive and ‘cool’ as the artists he fosters and campaigns for.

Many of the above aspects of his daily work could be defined as standard gallery activity, since galleries build careers of young artists by supporting, advising and promoting. Yet, what sets Simchowitz apart is thus something else, namely his ideology of the art system. In his universe, the enjoyment of collecting lies in play, speed, visibility and financial profit, in ‘the here and now’ as opposed to the classical long-term drudging through hermetic artistic oeuvres with a glimpse of cultural prestige as reward. Simchowitz encourages his clients to trust his authority and not to waste too much time in order to research their personal taste or to develop their own subjective vision on art. In his recent interview with Artspace Simchowitz said:

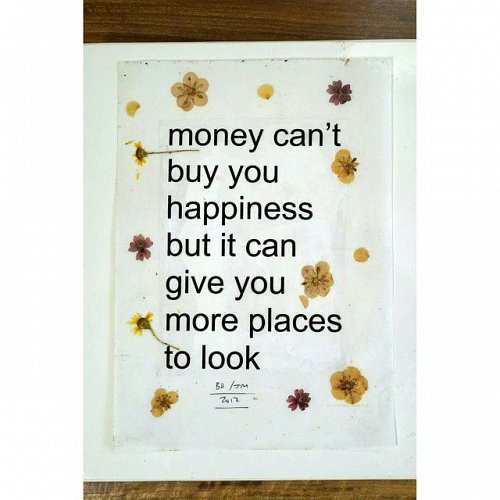

If I sell you something for a dollar and you sell it to your mate for two dollars and he sells it to his mate for four dollars, and he sells it to his mate for eight dollars, and he sells it to his mate for 10 — well, that’s five collectors who bought the work, discussed the work, studied the work, and made a profit from it. And then they feel good about investing in cultural production, which is a very difficult thing to do because art, at the end of the day, has no value.

This is a provoking statement since Simchowitz doesn’t deny the morally high-valued idea of the pricelessness of artworks. However, in opposition to the traditional reading that condemns the market as a mirror of artistic value, he states that he uses the market to create a platform upon which the priceless cultural production can take place at all. He justifies his commercial operations by the argument of genuine interest in artists’ development and participation in making of the culture of one’s time. In passing, by promoting re-selling he shifts the focus of collecting from permanent to transitional ownership.

Reactions from the galleries and critics were easy to predict: he is a flipper, he doesn’t understand art at all, art has nothing to do with money, he is barbarian and actually every word spent on him is a waste of time. But, is it really?

Simchowitz irritates in the first place because of his blunt statements and aggressive behavior. When he approaches particularly young gallerists to sell him works by their artists, the conversation starts with compliments about the program, but can quickly turn into a series of offences. If the gallerist doesn’t want to sell works he is told to fuck himself or at least to get over the bullshit and to join the real world. Simchowitz then often moves toward the artist in question, speaking to him or her directly and commenting on their gallery as provincial, narrow-minded and amateuristic, while presenting himself as the only one who can make the artist rich and place him in important American collections – as Europeans don’t really count. Some artists detest it, while some accept.

What this annoying method disguises however is that Simchowitz’ ideology attacks the moral fundaments of the art system as it has functioned from the 19th century onwards. The system defined a good collector as one who is principally disinterested in money, the artist as living for the sake of art only and art as being useless in the practical realm of human activities. Throughout the 20th many theories presented art as something that transports the viewer above the stream of life; a world in which no human interests are relevant, money being the worst. These kinds of ideas, which reverberate in the art world until today, provided guidelines on how to behave in the art world, as well as classification tools to distinguish a philistine from a cultivated art collector.

Simchowitz exemplifies that these qualifications between good and bad have become problematic, just as, for that matter, many other concepts that formed the principles of the modern system. The Avant-garde concept has quietly died out; artists have embraced the big audience, they don’t want to bash anybody and hardly any artist calls the upper and the middle class despicable. Instead artists claim to provide a platform for reflection, and they declare the viewer – who has become an abstract factor, and who is no longer regarded as belonging to any particular social class – as essential for art’s meaning. Furthermore, the system of authority has started to blur, as art critics lose confidence in defining the relevance of art, and museums are now more focused on scaling up their programs to global dimensions and other issues.

It is in this fragmented field of authority that Simchowitz attempts to be a new Clement Greenberg, someone who tells others to follow him because he knows what good art is. The comparison to the influential American critic is perhaps too far off, as Greenberg gained his prestige through a clear formulation and consistent enforcement of new aesthetic rules that fitted within the artistic and social requirements of his time. However, the acquisition of authority today doesn’t seem to depend on the control over aesthetic principles as such, rather, it stems from a solid and exciting distribution of opinions and images with prospects of emotional and financial returns, which is the expertise of Simchowitz.

A statement of one of his client, an actor and producer Enriquo Marciano exemplified in which manner Simchowtiz has been building his status and the base of his followers:

If he says to buy something, I buy it. I don’t need to know the size. Yes, many times I’ve bought things without liking or disliking it or even seeing a picture. I bought Oscar Murillos when they were $500, Joe Bradleys when they were $6,000, Ryan McGinleys when they were basically free.

Simchowitz links his authority to the value increase of works that he has advised to his clients. But what is at stake here is the ideology of collecting, for Marciano admits publicly that he buys without having an opinion and without personal commitment to art, whilst mentioning prices that give an indication of the huge profit that he would have made out of his early blindly made acquisitions. There is no personal choice, nor a subjective meaning; still there is enjoyment and the idea of involvement through success. This is not an innocent statement though. If these collecting attitudes were to thrive, and if money were to be allowed as part of the morally accepted enjoyment of owning art it will in the long run ruin the existing art system, which would need to redefine its moral rules anew.

The Internet has introduced tremendously influential new possibilities by creating new ways of exchange, alternative networks, and authorities. Simchowitz was able to develop his activities only thanks to Internet and social media, which helped him to quickly circulate images, distribute information, create his media personality and reach a larger public. By using these possibilities he attempted to establish an additional distribution channel and a new collecting attitude. The distribution of images and its public consumption is where the essential meaning of Internet lies for art, not in the new technical possibilities of images. The recent hype of internet-genic young abstraction demonstrated the operation of rapid distribution, serial production and enjoyment of reselling.

One can say that Simchowitz is a joker but one can also say he – as a phenomenon – continues making transformations that were observed by artists such as Quaytman. By rendering the invisible visible and breaking open of the myths of artistic production, by making artists and others aware of the fact that there is no morally clear outside – which is observed by another Orchard Gallery artist, Andrea Fraser—are phenomena that all contribute to the disintegration of the existing system by a new movement that Simchowitz is a part of. We are facing a change – there is no question of whether the art system will change, the only question is how.

Art history will be kept alive and connoisseurship will survive among experts and those who care for it- no worries about that. Nor are we becoming dumber and more superficial as various scaremongers want us to believe. Instead, we are facing transformations of the art system: the opposition between the elite and mass has turned out to be outmoded and no longer sufficient to explain what is going on, while the idea of collecting for ever has been defied by collecting for now. Measuring art value with money will not disappear, as money is the easiest way to speak about values in art for those who don’t have time or other skills to express themselves. Therefore stop fulminating against the moral corruption in art because of its relation to money, as it is useless. A much more interesting question is, what moral instruments can we develop to adjust the art system to new challenges of distribution, accessibility and newcomers, who don’t necessary enjoy traditional rules of collecting?

Correction: According to S. Simchowitz the amount of money due to the sale of Media Vest has been much lower than the 200 million reported by various media.

Photos taken from the Instagram account of S. Simchowitz.