Breaking the code

Published: January, 2014, INTRODUCTION TO THE BOOK "MADE IN MIND"

What all the artists have in common is that they operate in the same vast field of contemporary art. This means that each one of them has to find her or his own way in the seemingly open artistic playing field that is by and large not limited by any formal rules or discursive norms. The legacy of the radical act by Marcel Duchamp, who at the beginning of the twentieth century declared an industrially produced everyday object an artwork, made it possible to call any object an art object. This turned out to be at once emancipating, challenging, and intimidating. It gave the ultimate power to the artist, since from that moment on he was seemingly the only deciding factor regarding the status of an artwork, liberating it from any formalistic criteria. Yet, at the same time, the Duchampian formula of the readymade — an object deprived of any aesthetic conditions and personal emotions — emerged as the basic obstacle to formulating any clear qualitative criteria regarding contemporary art. The fact that everything, every idea, let’s say every trace of human activity that has been conceived as an artwork or declared as such by the artist makes any categorizations redundant and any judgement arbitrary. Thus anything goes, or at least anything could go, but how to make it go seems to be very complex. Therefore the important question today is not “Is this art?” but “Is this good art?” and if so, what makes art good art?

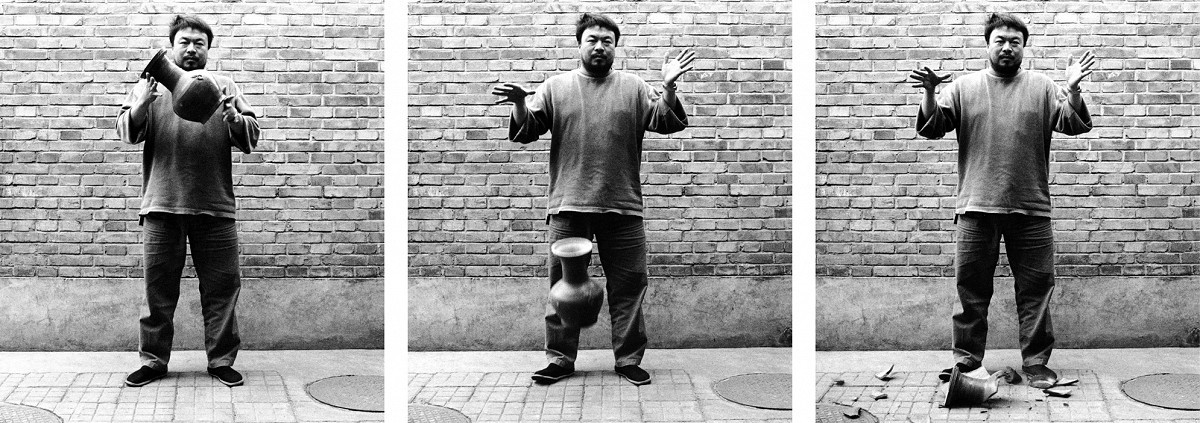

The Duchampian anti-academic negation of the possibility of meaningful “retinal” art expelled it from the traditional field that art was supposed to inhabit — the one of beauty. Obviously beauty has always remained a point of reference for artistic practice but after the subversive act of Duchamp it had lost the self-evident core characteristic for art. The after-effects of this process have reverberated throughout the twentieth century till today. As a result, many artists are nowadays more interested in breaking a code, solving a riddle, challenging a system, than in providing the viewer with an aesthetic experience. Often including a self-reflexive component, contemporary art thus oscillates between a celebration of the immense opportunities of today’s world and a dialogue with the great traditions of the past that are being translated into the seemingly limitlessness of current discourses. The danger is, however, that this anything-goes formula, full of questions without answers and overwhelming interreferentiality of images and concepts, has in the meantime become academic and repetitive itself. As Thomas Schütte critically remarked in the interview in this book, many contemporary artists lack the sense of urgency and the will to act, but tend to switch between various available options, simply looking for fitting solutions for their optional artistic practice. This is where the question arises whether today’s Duchampian academism can avoid becoming a recipe for insignificant forms in the long term.

The Visionary Outsider

What does it mean to be a contemporary artist then? What historical traditions have formed his identity today? Does his position somehow mirror the society of the twenty-first century?

The widespread myth of the artist wants us to believe that the artist possesses some auratic magic properties, a kind of sixth sense or a transcendental antenna that allows him to feel all kinds of transformations in society that are invisible to its other members. The French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu credited the circle of a few nineteenth century French artists with the invention of the charismatic persona of the artist, with his indifference towards money and his status as an outsider. To understand this concept better we need to go even further back in history to the end of the eighteenth century when the philosopher Immanuel Kant in his Critique of Judgment (1790) connected the aesthetic judgment of beauty with the principle of disinterestedness. That means that the judging subject, the viewer, does not experience any form of desire for the judged object, the artwork, and moreover, that the object doesn’t generate such a desire. By declaring beauty as that which pleases without interest and understanding, Kant simply placed art outside the fields of desire, knowledge, and morals, an idea that forms the basis for the autonomous position of art and the artist to this day.

Similar ideas on art also reverberated in writings by several German Romantics, who saw art as an important factor for the development of the human condition, since beauty was able to refine and ennoble human emotions. In Über die ästhetische Erziehung des Menschen (1793) Friedrich Schiller stated that “man only plays when he is in the fullest sense of the word a human being, and he is only fully a human being when he plays.”4 Play, as he understood it, was literature, art and, from the social point of view, rituals and the will to symbolize. This implied freedom against utility and rationality, which Schiller considered to be dangerous elements of bourgeois society because they enslaved talents and undermined the power of the arts. For art, according to him, was an aim in itself, comparable with religion, love, or friendship; Schiller claimed that art wants art as love wants love without the will of being useful, whereby the social utility of these phenomena is essentially a by-product.

This notion was further elaborated on in the second part of the nineteenth century with the Parisian L’art pour l’art theory. Originally developed in the literary field and promoted by the writer, journalist, and critic Théophile Gautier, the theory claimed that art should limit itself to the issues relevant to art only and not try to justify its existence by any didactic, moral, religious, or social functions. In the field of fine arts the theory helped to develop the awareness that was needed for the development of various new movements, which investigated the formal and ontological qualities of art, such as Impressionism, later Post-Impressionism, or Cubism. However, the theory had many social consequences since it also positioned the artist, indirectly and probably inadvertently, within the new capitalist structures that seemingly liberated him from his dependency on commissions as his basis of living. The liberated artist could create freely and experiment formally, but the price he had to pay for it was a financially troubled existence, which he was compensated for by the prestigious model of the artist as bohemian. Bourdieu suggests that the bohemian artistic ideas expressed in the works of Charles Baudelaire, Gustave Flaubert, and Edouard Manet around the mid-nineteenth century were important for the formulating of the professional ethic of the bohemian avant-garde that meant a break with the traditional academic eye. The social position of the bohemian artist has become that of the outsider, but an outsider with an aura, sometimes of a romantic visionary, sometimes of a revolutionary with a social mission.

A few theories related to art, which emerged at the beginning of the twentieth century helped to cultivate the exclusive position of art in comparison to other social fields. The so-called Significant Form theory, proposed by the philosopher Benedetto Croce and the critic Clive Bell, was quite influential on the thinking on art of the first half of the twentieth century. In his essay What is Art? (1913) Croce defined art as vision or intuition, which implied to him that art couldn’t be physical, utilitarian or moral, nor based on conceptual knowledge; art is ideality that signifies and in which the concept is resolved in the universally recognized form. Elaborating on the ideas of Croce, Bell searched for the unique quality of art that is common to all artworks, and concluded that this quality is the significant form. Art transports the viewer to “the world of aesthetic exaltation” and “above the stream of life;” a world in which no human interests are relevant and no descriptive qualities are needed. Bell claimed that for the appreciation of a work of art one needs only a sense of form and color, and knowledge of three-dimensional space whereby the representation was more the weakness of an artist than an additional value in providing an aesthetic emotion.

Analyses on art and the artist by the English art critic, art historian, public intellectual, and multidisciplinary scholar Roger Fry form an interesting example of how this formalistic concept nourished the notion of the bohemian artist. For Fry art is a special field: “We find here [in art] a purely spiritual activity analogous to that which impels men to search for truth. It is this pure, free, and biologically useless activity which has produced those works which are among the most cherished passions of mankind.” Fry tried to categorize what he considered true art and not true art, and therefore introduced a distinction between true artworks: objects in which one can trace “the quality of expressing a particular emotion called the aesthetic emotion” and opifacts, being objects made by man but for the gratification of some special feelings and desires, the first stage of advertisement. In Fry’s system, artists and artworks occupied a different position from opifacts and opificers, the makers of opifacts. In the course of the history of art there was always a distinction between “the pure opificer who is immune from aesthetic feelings and the pure artist who has no possibility of compromise with commerce and existing order.” In this judgmental statement Fry suggested a negative relationship between the true artist and his commercial success. Incidentally, it is interesting to notice that around the same time Duchamp was producing several of his Readymades, a concept that, as mentioned before, aggressively defied the retinal aesthetic experience. These formalistic/aesthetic and anti-formalistic/anti-aesthetic artistic approaches, opposing each other but both situated in the autonomous field of art, live together and fight against each other to this day.

The economist John Maynard Keynes, a good friend of Fry’s, was also involved in thinking about the role of artists in society, but his involvement was based on different motivations. His biggest concern was namely the bad financial situation of artists, which Keynes wanted to improve through a better implementation of artworks and artists in the economic system of his time. The solution was, according to him, the promotion of an interest in art in the middle class and a better accessibility of artworks to a broader public. For us the most interesting point in his considerations was his view of the artist in general, whom Keynes didn’t consider as economically suitable to the new system: “The position today of artists of all sorts is disastrous. The attitude of an artist to his work renders him exceptionally unsuited for financial contacts. His state of mind is just the opposite of that of a man the main purpose of whose work is his livelihood. The artist alternates between economic imprudence, when any association between his work and money is repugnant, and an excessive greediness, when no reward seems adequate to what is without price.”13 This statement illustrates the way in which the cliché of the artist as outsider and the value of his art had proliferated further and increasingly become taken for granted. It is an example of the common opinion that the task of an artist is to be involved in the making of true art, which is of no use other than in the realm of aesthetics, that his involvement in economics is inadequate, and, last but not least, that the pricelessness of art and the difficulty to determine the financial worth of an artwork are inherent to the identity of a true artwork.

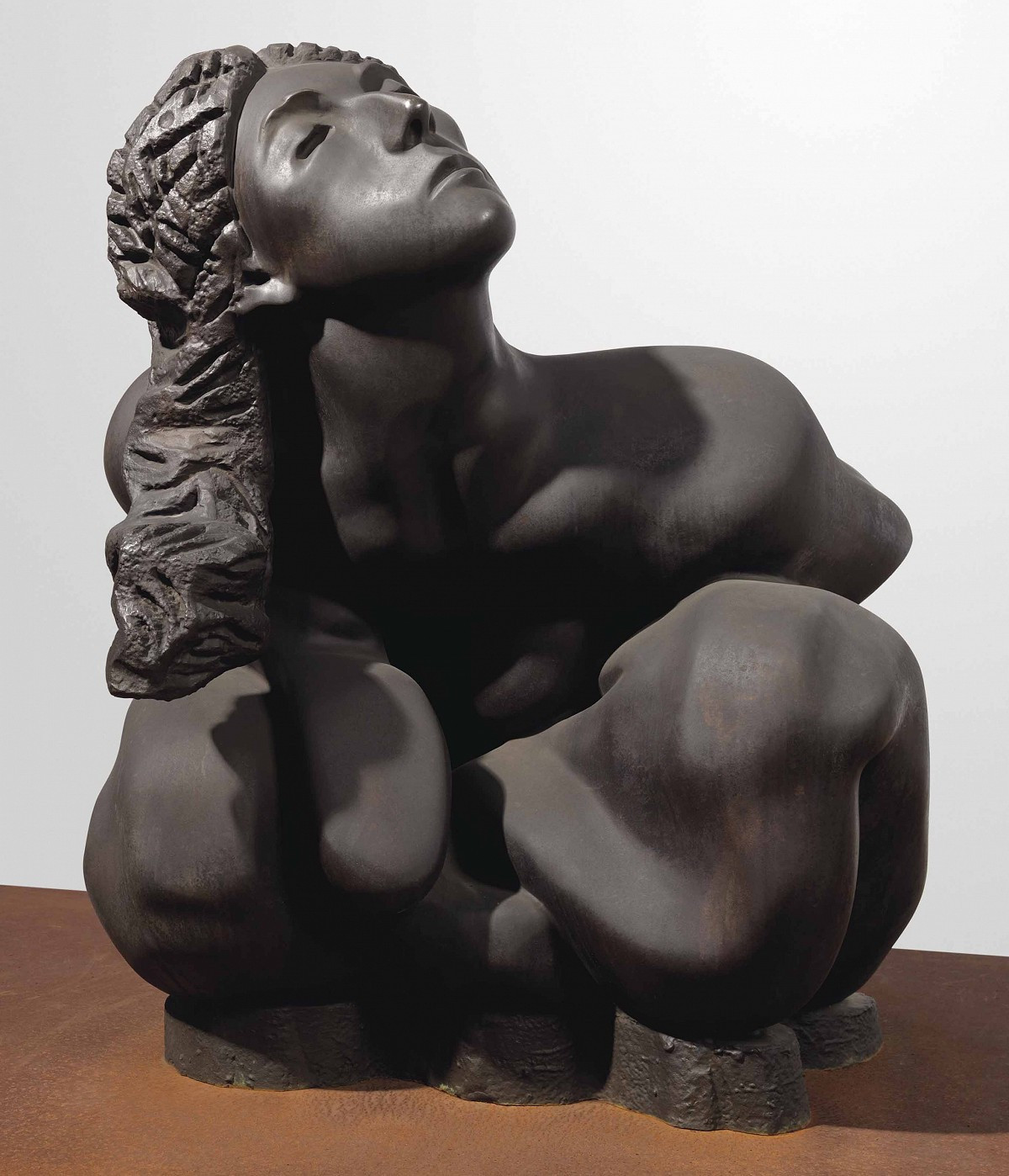

It is not my intention to present a historical review of the developments of the notion of the artist as someone who operates outside the stream of normal life. Instead I want to stress that this idea has survived right up to today and, alive and kicking, still forms an indivisible part of the common social ideology about the artist. Sometimes this ideology is encouraged by artists themselves, as the definition of an artist given by Andrei Roiter shows: “being an artist means being an outsider who is breaking the rules.” Also the artist duo Elmgreen & Dragset considers art to be a phenomenon that aims at confronting, seeking contradictions, and de-fixing codes although they refuse to credit the artist with inherited magic properties: “I’m not a medicine man; I’m not a shaman.” Still, although various discourses throughout the twentieth century have attempted to deprive the artist of his special position and auratic features, these attempts seem to have failed in the long run. Cherishing the tradition, many art consumers tend to consider art as a special space in which the artist can perform social and personal miracles. This opinion is backed by numerous artists who continue to relate their practice to the concept of art as the realm of extra-ordinary properties. According to Ai Weiwei “art is not a territory but magic. We cope with our lives so we should not be away from our consciousness and our passions.” Terence Koh uses the “auratic” notions as part of his artistic ideology: “artists are the most supreme form of intelligence in the world, in the universe. we have ability to rule the universe. we must find the ways, collect our thoughts so that a sculpture or sound artist can be president of the united states or installation artist is the prime minister of india. there is power. there is the world change, we have to start talking. creating actions.”

The last mentioned aspect, creativity, has received additional attention in the current era of the creative industry that has been expanding since the beginning of the new millennium. Artistic creativity has become a quasi-economic asset, which the artist can exchange in other fields, outside of art. Since, in this highly efficient world, the artist is able to create concrete value out of symbols, he could stand as the model of ultimate inventiveness, the prototype of the “creative non-conformist.”14 Consequently, the auratic qualities of the artist are sometimes translated into the creative universal powers and in this shape seem to find new ways to function in society. We can find examples of companies that have been trying to use the creativity of the artist in their corporate structures by simply implementing artists to see “things and processes differently.”The dialogue with artists is meant to broaden their thinking horizon as well as providing insights into the economic field; as BMW’s chief communications officer Christiane Zentgraf stated when defending the claim that the economic sector needed art and culture: “Through the contact with art and artists we have the chance to become more sensitive and sophisticated, to sharpen our perception and sensory sensitivity and to look ahead of time.” This statement is exemplary for many companies, which have been involved in supporting art. According to this view, the presumed artist’s visionary properties could be explained as creative values that are supposed to trigger processes according to a different logic than the economic one; processes that could possibly change corporate structures from within. See here the combination of the notion of the historical aura with the avant-garde politics applied within the socio-economic context in which creativity has acquired a commercial value. At the same time, since creative power and innovation have become the programmatic core characteristics in other professional fields as well, creativity seems to be a bridge between the artist and other areas of social activity. Joseph Beuys’s statement “Jeder Mensch ist ein Künstler,” that implied a creative potential in everybody, sounds like a confirmation of the crucial relationship between the artist and the nowadays compulsively creative outside world, where creativity has been professionalized.

While creativity presupposes a shared experience between the artist and the rest of the community, the imagination of the artist remains nevertheless at the service of symbolic cultural production. As long as art can shape a distinct ground to explore individual fears and desires, the public wants to see the artist as a magician who can offer temporary redemption, revelations, and solutions, or at least a suggestion of them. Art has remained a territory in which the big existential issues of life can be questioned in a manner that is neither conventional and nor rational. Therefore we want the contemporary artist to be an artist by birth or by instinct, and not by choice.

To Change or to Reflect

Let’s go back to the notion of the autonomy of art that has been made explicit by the “L’art pour l’art” theory since it has turned out to be one of the main complexities of today’s artistic practice. Trapped or blessed by this concept the contemporary artist inhabits a so-called independent public sphere in which no social rules or communally useful categories seem to be applicable. His position in relation to other fields of human activity has developed into a complicated issue that is of great relevance for today’s art reception and production. The question, how to reconcile the credo of autonomy with the practice of everyday economics and the need for social engagement, knows many different answers.

This tension had already appeared during the early avant-garde movements of the twentieth century when new movements sought to connect art with social and political transformations. Those avant-garde movements aimed at implementing art as a progressive instrument with an artistic but above all a social potential that reflected indirectly on the processes of modernization and the new social order. Futurism (“a roaring motor car, which seems to race on like machine-gun fire is more beautiful than the Winged Victory of Samothrace …”)], Suprematism (“No chambers of the academies will withstand the days to come… Angelo’s David is a deformation.”) and Dadaism (“Dadaism for the first time has ceased to take an aesthetic attitude towards life, and this it accomplishes by tearing all the slogans of ethics, culture and inwardness, which are merely cloaks for weak muscles, into their components”) all expressed extremely hostile attitudes towards the old art, the bourgeois social order, its values and moral principles. Art was flirting with the idea of the destruction of the existing antiquated systems thanks to the conviction that the rebellious artist had the gift to change society through his art and was able to develop a better world.

While these movements died relatively quickly, the revolutionary attitudes kept coming back time and again during the twentieth century in various modified forms; the conviction that art has the potential to provoke social change also forms a part of the ideological programs of many of today’s artists. Artur Zmijewski, who as well as being an artist was also the curator the 7th Biennale in Berlin in 2012, tried to investigate the position of the artist in the social and political field. For him it is untenable that an artist claims not to have a political position. Zmijewski’s goal is therefore to combine artistic autonomy with an urge for political involvement that could give art “the real” power in society; a power that is able to bring about some significant social and political changes. How radically the positions of artists can differ is, however, illustrated by the attitude of another of the interviewed artists, Urs Fischer: “I think that most art dealing with politics is either deliberate propaganda or a case of an artist feeling unable to participate in politics and trying to make up for that. I don’t think propaganda is a forte of art-making anymore. Art is an after-reflection, not a frontier, otherwise Cubism would have begun in 1850 or earlier.” The statements of these two artists illustrate that there is consensus neither on the issue of artistic autonomy, nor on the function of art in general. While Zmijewski considers contemporary art as a field with the possibility of political struggle, Fischer sees art as an after-reflection; while Ai Weiwei cannot agree to treat any aesthetics separately from political and moral judgments, De Rooij states that art and life have nothing to do with each other because art is artificial and self-referential. Another interpretation of social involvement is given by Gabriel Lester, who considers his work as committed not because it deals directly with specific political or philosophical topics, but because by challenging looking and interpreting in general, it offers tools to enable one to think differently about political and social issues. For Elmgreen & Dragset art can change a lot, not by forcing changes, but by providing a possibility to open up someone’s mind. Also in the case of Boris Mikhailov, who succeeded to photographing the radical transformation in post-Soviet society, the connection is made through the work; for him photography discloses more than one can see in real life and therefore helps to better understand some undefined and hidden social processes. The painter Valerie Favre, who in her works addressed among others the uncomfortable issue of the universal right to suicide or the seemingly old-fashioned problem of the inferior position of women, sees the artist as a person who should warn about the complexity of some issues, explore them, and provoke discussion on social issues.

What is striking in regard to the question of social involvement and the artistic autonomy is that the artist almost by definition has always been a solitary creator, an individual who eventually can decide to engage with others but generally works alone. This is a big difference compared to science, which is another territory that, like art, has been detached from everyday life. For the physicist Dijkgraaf the big difference between art and science is the idea of cooperation. If an artist does something interesting, then that area is already occupied and there is no wish for someone else to join, although it obviously happens but more like copying than adding. While most artists want to be individualists, Dijkgraaf sees science as being more like a tennis match: “I respond to you, you to me, and we keep hitting the ball back and forth to each other.” While scientists spend a lot of time listening to the ideas of others in order to develop them further, in general artists celebrate originality — despite all the efforts of postmodern theory — and prefer to search for individual solutions.

The diversity of opinions about the position and involvement of the artist in other fields of human activity suggests that in general the artists treasure the notion of autonomy as the principal context of their art, although for some of them this independence can sometimes feel like a heavy burden since it deprives the art field of a direct social meaning that leads to immediate actions. We could think the autonomy principle in a different direction. The art theoretician and philosopher Boris Groys suggested that real autonomy is now experienced more in the context of the art market than in art institutions. In his view the presentation of artworks in the institutional context automatically creates a meaning that is provided by the given institution or invented by curators through the frame of the exhibition, which generally threatens the original autonomous existence of the work. Otherwise, the sovereign decision of the buyer to pay what ever he wants to pay for a work is comparable with the sovereign decision of the artist to make whatever he pleases.20 This interesting remark applies, however, only to exceptions between artists and art buyers, the majority of whom are captured in the networks of artistic references, prevalent values, and social dependencies. Still, following this train of thought a bit further, the art fair would be a better place to experience the autonomy of art than the museum because at the art fair different works hang next to each other, detached from the oeuvre of the author, the meaning of an exhibition, and the signification of the proper exhibition space. Obviously, also in this case there are no bare meaningless walls of the gallery booth where the works compete with each other in their equal autonomous existence; the gallery name creates the context of meaning and value but only for those who know.