Arcmanoro Niles

Published: November, 2022, Arcmanoro Niles on Art and the Question of the Good Life

Marta Gnyp: I'm very curious about the works that you have been working on recently, but let’s start with a bit of history. The earliest works that you published on your website date back to 2012: figurative paintings with preference for dark colors and heavy subjects, like illness and loneliness. You can sense that the paintings were made by a good, young, skilled, talented, and ambitious painter, but there was not much difference between you and other skilled and talented painters. Then around 2015, also the year you graduated with your M.F.A. from the New York Academy of Art, something happened: the colors in your paintings exploded! What had so dramatically changed your color palette and the imagery?

Arcmanoro Niles: I was always very interested in color, and I was always trying to figure out how to bring out the color inside the flesh tones that I saw. If you look at the painting Infinite Regression (2012), you can see an old man in a hospital bed laying on a pillow; his chest has traces of red; the pillow and the bed are kind of pink. It's because I started with crimson underneath. As time went on, I stopped painting people, because I wasn't able to get the colors I wanted. Instead, I made paintings of space stations or landscapes, where the figures were fully clothed and turned away from the viewer. Around this time, I began to put sculptures in my paintings, too, so I wouldn’t have to deal with skin. The last painting I did in grad school, The Field of Sacred Duty (2015), was the first portrait I had made in a while, and I let some of the ground show in the eyes of the figure. It was a bright red. From then on, I started to become more comfortable with letting the colors shine through.

MG: But the breakthrough moment came later.

AN: The following year, I was painting a self-portrait from a photo that was a bit orange. In school, I was taught to first make a painting brighter than it needs to be and then dull it down to get a very strong contrast. But I was never hitting the color I wanted; because I was adding colors on top of neutrals, the starting point of my paintings was already dulled down. I thought, what if I start with really bright colors I like: orange, various yellows, purples and reds and then add the neutral tones and browns later? For some reason, the color felt more real this way than it would have if I had tried to make it look realistic.

MG: It makes sense. Realism doesn't necessarily mean that it should be true to nature.

AN: When you try to paint flesh naturalistically, you can still tell it’s fake. The image is trying to be something that it never can. When I let naturalism go, the works ended up feeling more real to me.

MG: Intriguingly indeed, your characters with red eyes, pink hair and golden skin are people of flesh and blood. Where does the image start? Does it start in your head from your imagination or memory, or does it start from observation? Or maybe from existing images like photographs?

AN: A lot of images refer to my own experiences or what I’ve imagined from the stories other people have told me,The image is usually not completely made up from my mind. Often I use old family photos, or sometimes I'll bring someone in and photograph them, and then use that as a point of reference.

MG: You would stage the scene with people and take a photograph.

AN: Exactly. In 2016 and 2017, I was going back home, where I hadn't been for a while, and I was just thinking about my neighborhood. To compose the playground scene in The Classroom (2017), I got some of my friends' kids and asked them to pose for me, but the work ultimately is based on my own memory of the playground.

MG: Let's speak about the color because, as you already mentioned, color has been such an important issue in your work. When I was reading the reviews of your previous shows, the descriptions of your color palette were very telling: “radioactive,” “radiant,” “electric,” “vibrant,” “neon,” “toxic.” You just mentioned one of the reasons for this choice: it allows you to paint figures in a way that feels real to you. Is there any other reason that you have chosen colors with such effects?

AN: In high school, I used to make these abstract paintings inspired by Rothko. I wanted to use colors to get emotions across. In my first portraits, instead of using black and white, I used purple and white. I've always been interested in deep reds, crimsons, purples, and other bright colors. When I was a kid, there was a TV show called the Fullmetal Alchemist, in which an alchemist was chasing after a philosopher’s stone. It was this bright crimson stone. To me, that color sort of represented life.

MG: You are perfectly aware of art history, so I wondered whether the long tradition of color symbolism in Western art has somehow influenced your thinking. In the Middle Ages, Renaissance and Baroque eras, colors carried symbolic values related to Christian imagery. For example, red was the color of blood and martyrs, which meant love and salvation. Then we had several theories of colors, like the one by Goethe, who thought that colors have a certain meaning, or by Kandinsky, who proclaimed that colors evoke certain moods. Red is, by the way, considered a very important color by all of them. Have any of these connections hovered in your mind?

AN: Well, I can't say those references were at the forefront of my mind, but just because of my more traditional training as a painter, those connections are there. I really like Caravaggio, so I was always looking at his use of color and symbolism. I even copied a few of his paintings.

MG: Really?

AN: Yeah. I started off by putting myself in his paintings. The first one I did was David with the Head of Goliath (2009).

MG: Both figures have your head.

AN: I drew myself as both of them, because I felt that there was a little bit of both David and Goliath in all of us. When I first saw Caravaggio’s work, I understood that it wasn't only about religion and sacred images; it was also about his life in Rome and his everyday life, using the Bible as a framework to depict how things were that day. I really liked that and started doing that with myself and people I know. In the Magdalene drawing [The Death of the Virgin (2009)], that’s my mom, and that's me in the background. I also saw Simon Schama’s series, The Power of Art, and Schama talked about how Caravaggio painted himself as the villain as a way of asking for forgiveness and pardon.

MG: Do you somehow identify as Caravaggio?

AN: When I was in high school, I could identify with Caravaggio’s struggles, and that really stayed with me.

MG: Why did you identify with his struggle at that time?

AN: I've always felt that there isn’t enough time. My dad had me later in life, so I always had an older parent. In high school, I grew up with my grandparents, who, within four years, both got very sick. Then, my first year at community college, the doctors thought that I had HIV. I couldn’t believe it. They come back confirming that I didn’t have HIV, but then they thought I had cancer. I lived with the idea that I had cancer for about three months. Eventually, it turned out that I didn't have cancer either, but I remember at that time, I thought I was going to die. I thought, “I'm about to die a loser,” so when I got home after school, I started painting furiously. I stayed in my basement, and I painted. I felt it was important to try to leave something behind and to say something about who I was and how I lived.

MG: The confrontation with mortality was a push towards painting.

AN: Yeah.

MG: You have very often painted yourself in your works.

AN: Many paintings are self-portraits, but they’re more about representing the self to convey a particular type of universal experience and expressing those moments in life we all face.

MG: You very often build a connection with the viewer using different means.

AN: The paintings are usually about life-size, and you as the viewer are part of them; you're walking into the scene and connecting either with a person looking back at you, one turning away from you, or one inviting you in. Even if it’s a still life, you relate to the daily objects and how you move through everyday life. Those connections are important to me.

MG: Do you want your public to identify with what they see to let them feel empathy towards the characters they see and become directly involved?

AN: I think so. If I’ve been through a certain experience, or if I know someone who’s been through it, then someone else probably has too. Painting these scenes is my way of connecting with people, because in my normal life, I'm kind of shy. In a lot of ways, I'm kind of the opposite of my paintings: my clothes aren’t too colorful; I mostly wear black; I'm quiet; and I’m not so open in my day-to-day life.

MG: Your figures have shiny glittery hair, which is a source of light in the painting, but it could also be interpreted as haloes of perhaps contemporary saints. Are you trying to glorify the people you paint, who are often your friends and family? Do you want them to look like they come from historical paintings, to give them more authority, or to make them more glamorous?

AN: I was always highlighting the hair. It's been a big part of my life, because I've always had long hair. When I was making the painting When We were Young (2016), which shows a guy and a girl on the steps, their hair reminded me of the gold leaf halo because of the orange color I used. I wanted to use something that was colorful and not gold leaf, so I started playing with glitter. I wasn't trying to make them more than what they were. I wanted to show what was already there by adorning it or highlighting it a little bit. I do like this idea of the halo, but it wasn't meant to make them look like saints.

MG: You were rather experimenting with new formal or material solutions.

AN: There were already artists such as Chris Ofili and Mickalene Thomas, who were using beads and rhinestones. So for me, it wasn't too far of a leap. When I'm thinking about the skin, I'm thinking about how the light falls. Most of the painting is done in acrylic, except for the skin. That’s done in layers of oil paint. I'm always thinking about how the light bounces back to the eye. With the acrylic paint, the light hits the canvas and comes back right away. With the layered oil paint, the light comes back slowly and gives the skin a glow. I was wondering how else I could create this glow effect, so I started playing around with glitter. That's really where the halo effect came from.

MG: What about the seekers, those highly interesting, weird creatures that inhabit your paintings? We have two types: the first one is the see-through seeker, mostly involved in sex, and the other one is fleshier and gremlin-like and likes to harm either itself or someone else with a big smile on its face. Where does this idea come from?

AN: Let’s look again at The Field of Sacred Duty (2015). Do you see this sculpture in a kind of orgy scene at the bottom? This is an Egyptian fertility sculpture that I saw at the Brooklyn Museum. The museum text talked about how Egyptians used such works to describe the world around them. It wasn't just about sex; it was about rebirth, life, and death. Looking at it, I realized that I never drew upon anything outside of Western art in my work. I went to the New York Academy of Art and then to Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where the emphasis was on drawing from life and from Western sculptures. I became fascinated with these Egyptian forms, and I started using them in my paintings. As time went on, I got further and further away from the original sculpture, and over time, they became what they are now.

MG: I understand your fascination with its forms and concept but why did you create these two specific types of seekers?

AN: In 2015, I made Where I Can See You, featuring my mom. When I was younger, she was always nervous that I would go too far from the porch, that I’d get hurt, or later, when I got into high school, that I’d get someone pregnant. I wanted to find a way to represent these emotions and concerns that were present beneath the surface in a playful way in the painting. I like having these opposites. I wanted to have these cheerful creatures running around, just doing what's going to make them feel good. I was thinking about how violence, sex, self preservation, and all these different things influenced my upbringing and how I went about my days.

MG: They might also be a mirror to the viewers, who can see their own fears, desires, and longing for freedom through them. Cutting itself, what the fleshy seeker does is upon a second look less frightening, because it is about exploring borders of the body and experimenting, but it is also about trying to feel. You offer a very exciting puzzle to your audience.

AN: In The Classroom (2017), which shows a playground, there is this little creature. It’s like another fleshy seeker in the form of a condom. It was as a child on the playground that I first saw a condom, used and left there. The seeker is a way of capturing the unseen things that were going on simultaneously. I remember when I first showed the painting, two people said: "Oh, my playground was just like that. There were condoms everywhere." It’s a way of connecting to someone else who has experienced the same thing. Making this painting, I was thinking about myself at a young age. I don’t remember anything that I learned in the classroom, but the lessons I learned outside or on the playground about how to talk and interact with others stayed with me.

MG: Are you going to use the seekers in future paintings?

AN: I think so, but this year I didn't include them.

MG: Why not?

AN: I feel that my titles have gotten more specific, so it felt unnecessary. These paintings also felt more about what was happening right there in the given moment versus highlighting or calling attention to the past

MG: Your titles are often long and poetic. They function similar to the seekers in the image: they disturb, enrich, and expand the meaning. How do you invent your titles?

AN: Some of them are observations: words I hear and write down. Sometimes I'll hear a sentence that reminds me of something that's happened. I have this book with a lot of different notes and remarks, and I pull from it based on whatever feels right. A lot of times, the content and the image develop together.

MG: You grew up in D.C. in a district called Lincoln. Your solo show Revisiting the Area in 2018 at Rachel Uffner was described as a tour through the neighborhood where you spent your childhood and where you grew up. I’ve never been there, but your paintings depict it as a lower-middle-class environment.

AN: Exactly. I felt we were in this weird space in between the middle class and poverty. I guess the lower-middle class might be the word.

MG: You painted simple rooms with essential furniture, modest beds, no paintings on the walls, or signs of luxury. You imbued the paintings with attributes of the lower-middle class, but again, because of the colors you used, an environment that was neither rich nor splendid, looked rich and splendid.

AN: The buildings were made out of gold brick. The sidewalks were golden. In a way, my painting is the opposite of what the neighborhood actually was, but it was also a manner of expressing that this place was rich in a different way.

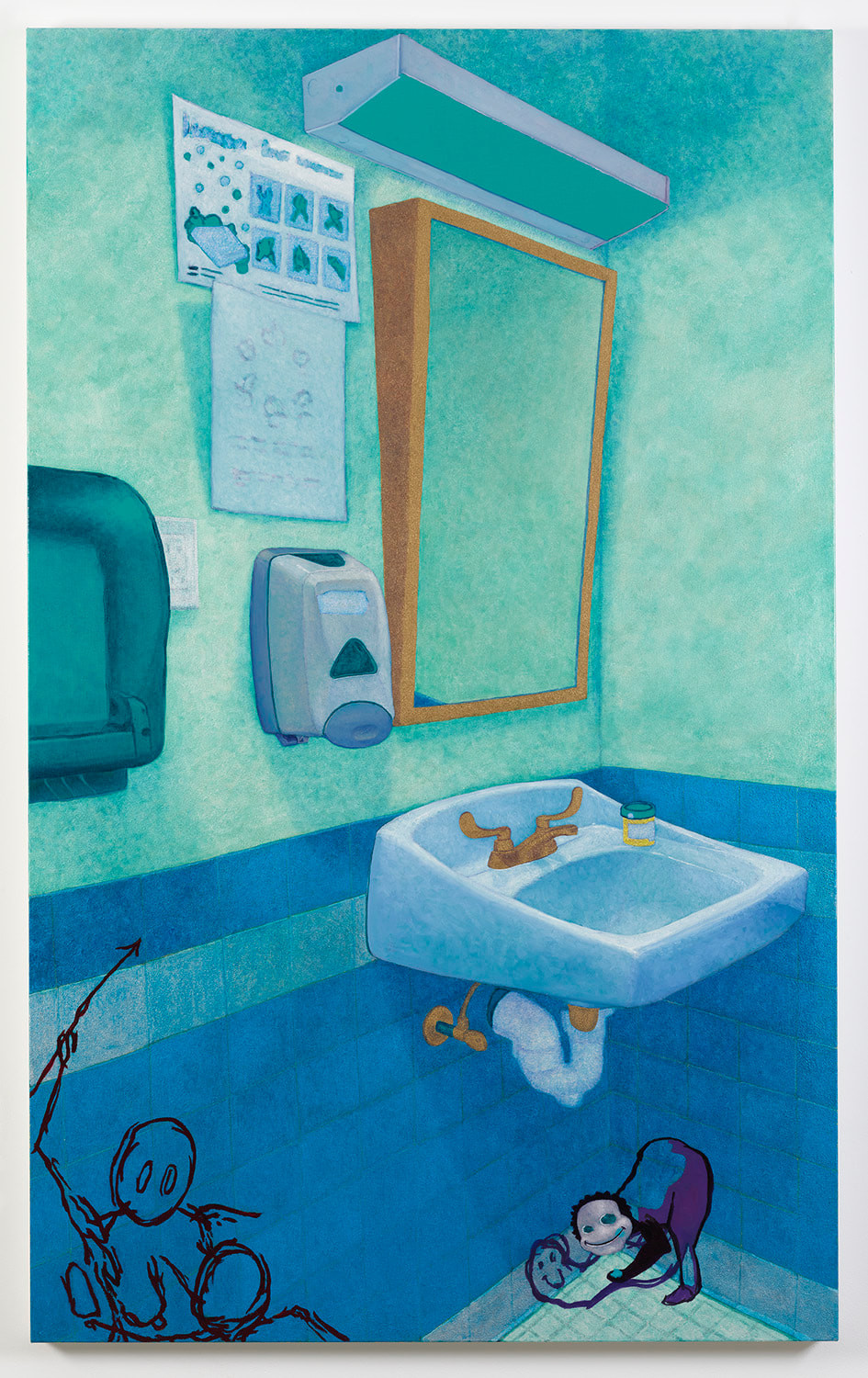

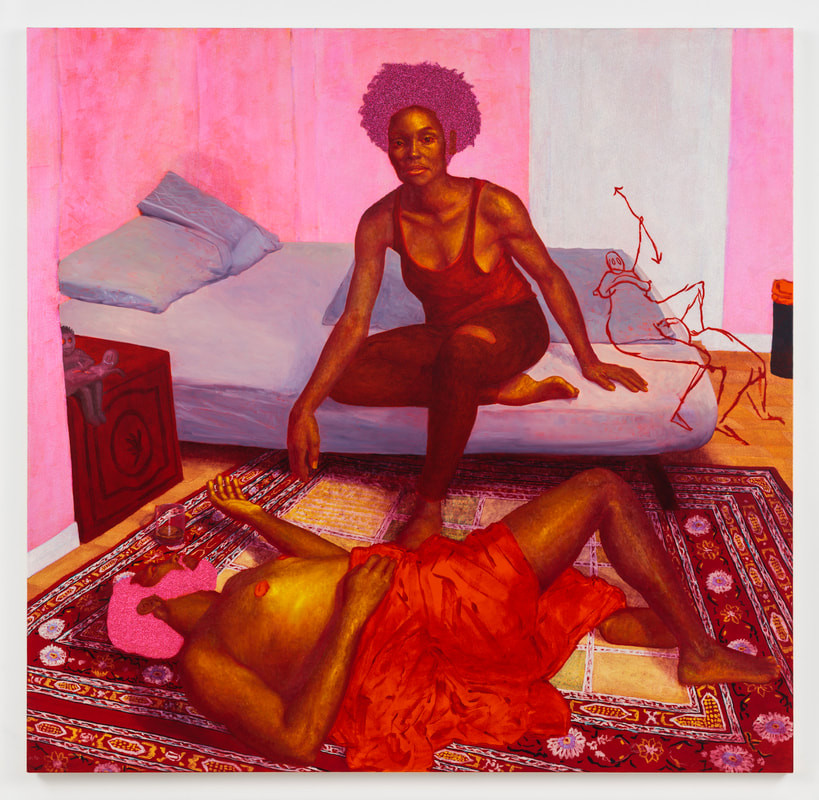

MG: What about your preferences for bathrooms and bedrooms as places of action?

AN Those are the places where I find myself thinking, standing alone with the mirrors around me, and where I see other people lost in thought. My solo show at Rachel Uffner in 2019, My Heart Is Like Paper…, was dedicated to these moments when people are contemplating and thinking about life and their past experiences. You as a viewer just walk in and catch them in the process. I was also reflecting on heartbreak–how it stays with you and can affect different decisions throughout your life, even when it's not quite as close anymore.

MG: Your last exhibition Hey Tomorrow, Do You Have Some Room For Me: Failure Is A Part Of Being Alive at Lehmann Maupin, New York was about failures, which is also a very interesting subject.

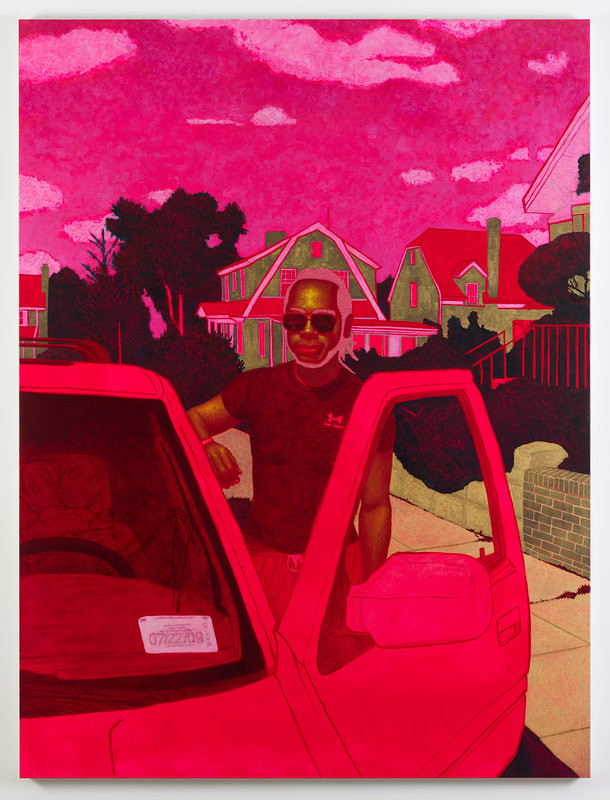

AN: I was thinking about those different moments in my life and other people's lives that looked or felt like big mistakes or failures but actually were moments that got you somewhere else. Take the guy in Kicked Out of the House for Living Fast (I Never Held Love In My Gaze So I Searched For It Every Couple of Days) (2021), or the figure in I Thought Freedom Would Set Me Free (And You Gave Me A Song) (2020). The guy who had a kid unplanned but becomes a great father, and it ends up changing his life. A good life, a bad life, you don't really know any of that until it's all over.

MG: I had an impression that that show was lighter and more joyful in comparison to your previous shows.

AN: Yes, I was definitely at a different place and a little older. Things changed.

MG: Speaking about change, we have to address the Black Lives Matter movement and the changes it provoked in the last years. Your characters are African Americans. Has this movement somehow influenced your work?

AN: Yes and no. In a lot of ways, it takes time for that stuff to catch up with me. Everything I'm painting is usually from before, and so I feel like I'm still processing what has happened. I think about it, but I don't know if it's shown up in my work just yet.

MG: Another big and unprecedented thing that happened during the last two years was the pandemic. I know it's too early, but was there something that you have experienced during the pandemic that you think somehow resonates in your work?

AN: I would say yes, but again, it's one of those things where it's tricky. Because of the pandemic, I feel like I said goodbye to a lot of things, people, places, and habits. The works in the upcoming show speak to that. The title will be: You Know I Used To Love You but Now I Don’t Think I Can: There Ain’t No Right Way To Say Goodbye Again.

MG: To whom did you say goodbye?

AN: My father passed away recently. Living With A Broken Heart Made It Difficult When I Was Young And Bullet Proof (It’s Easier To Miss You Than It Is To Let You Down) (2022) depicts him in a wheelchair. I was thinking about how sometimes it’s easier to focus on school or work than to go visit someone and risk disappointing them or to make them feel like they disappointed you somehow.

MG: Your father wears green-blue clothes that form a big contrast against the yellow, shiny background of a hospital room, as he holds his face in his hands.

AN: This painting shows him a few years before he died. It felt like the last time I would be able to talk to him. The times I saw him after that, he couldn't really speak. This moment, here, when I went to go see him in the hospital.

MG: Did making this painting help you close the chapter with your father?

AN: Painting helps me reflect, and I try to figure out why I do certain things and maybe why other people do, too. I’m interested in thinking about why people are the way they are and how small moments and decisions can impact and shape us.

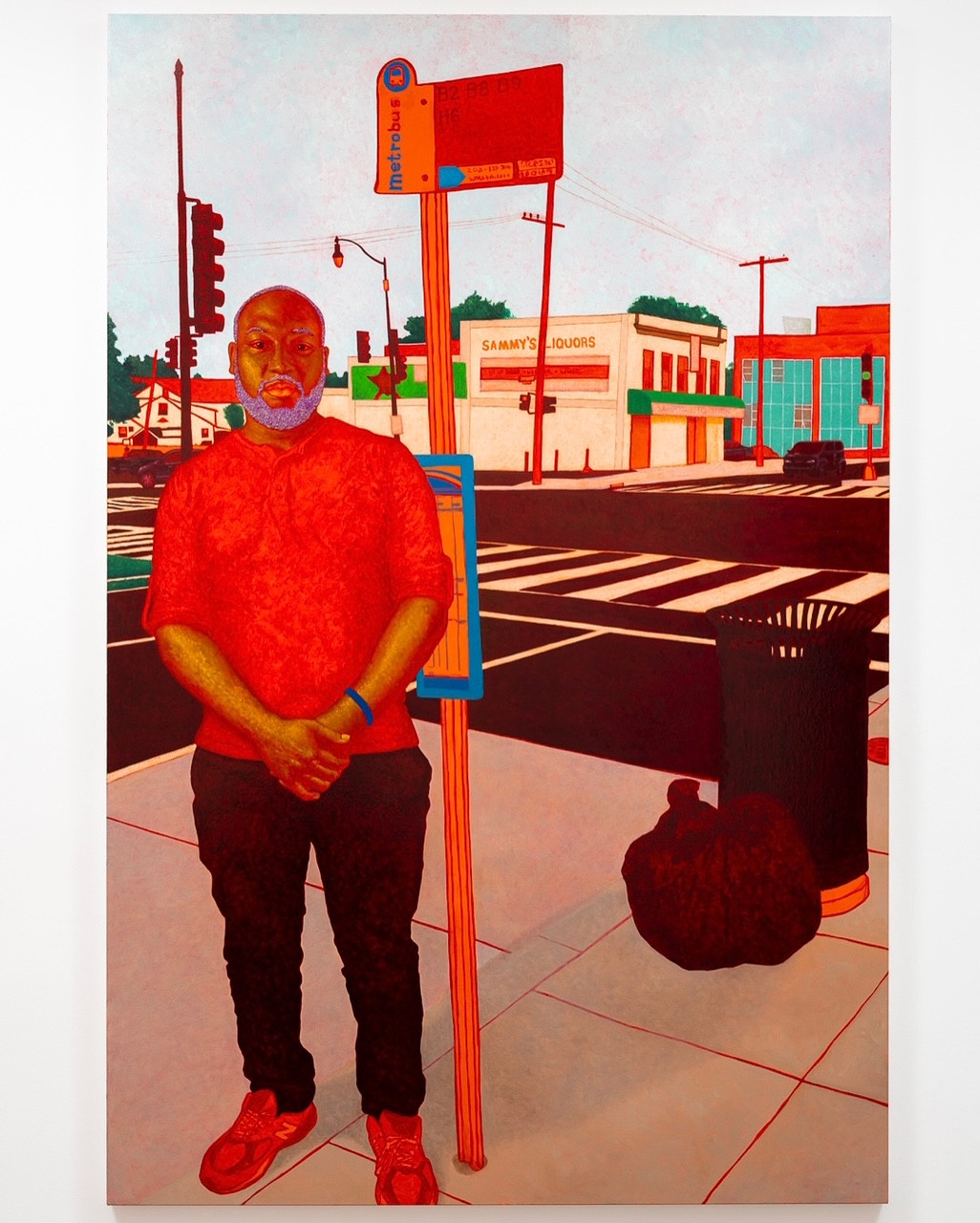

MG: Several of your recent paintings are now exhibited in A Place for Me: Figurative Painting Now at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, including In Between Real Love and Real Life (Remember When We Used To Meet and Do What Broken People Do) (2021), featuring a beautiful girl in a green dress, and What’s Life Without Scars (I Wear My Heart on My Sleeve and Be Tough When I Have To) (2021), depicting a man at the bus stop in a very dynamic composition of vertical, diagonal and horizontal lines.

AN: The guy at the bus stop is a friend from back home. His mom had passed away around the time when I was thinking about the goodbyes.

MG: Which brings us to a painting from your goodbye cycle, Growing Up May Be The Hardest Thing I Do (Healing Doesn’t Happen In A Straight Line) (2022). It's a striking self-portrait of you basked in illuminating colors, probably seriously thinking about getting older as the title suggests.

AN: It’s not only about getting older, but it’s also about the realization that if you want to change certain things, you’ve actually got to work hard. If you're going to mess up, that's fine; you're going to go back and forth, but then one day, you see that things are different.

MG: Growing older was also a subject of your earlier exhibition at UTA Artist Space, I Guess Now I’m Supposed to Be A Man: I’m Just Trying to Leave Behind Yesterday.

AN: It was the year that I was turning 30, and the whole time, I was thinking that by then I was supposed to be a man. Everyone makes turning 30 this big deal, but I really didn't feel any different. I was thinking about a time when I went to a doctor’s visit with my grandfather, who was sad because he had cancer. As a kid you don't think adults feel those things the same way. You think that nothing can harm them, so at the time, I couldn’t understand why he was acting differently. As you get older, you begin to see more. That was what the show was about: what does it mean to be an adult? I was thinking about different people in my life, who I thought were men, and the different times in my life when I thought I was a man, even though I was clearly a kid.

MG: From growing older, let’s go back to saying goodbye. Recently you made a still life, I Don’t Keep Liquor Here (I've Been Learning How To Do It All The Hard Way) (2022). We don't see any bottle in the painting, and liquor is conspicuous by its absence here. Did you part with drinking as well?

AN: I used to lean on it a little more than I should, partly because I spend a lot of time alone. But as I got older and to some extent got into more serious relationships, I recognized I had some things to work on.

MG: Another interesting aspect of this work is that historically, the still life showed objects understood as nature: fruit, vegetables, (dead) animals, flowers. In your painting, the nature is artificial: we see packed crackers and chips. It’s a contemporary still life that presents the artificiality of our lives, in which everything is precooked, prepacked, with no traces of life at all. There is also your landscape Always Had Me Under Your Spell (Some Things Ain’t Meant To Stay The Same) (2022). You haven’t painted landscapes that often.

AN: This is only my second one now. Recently I’ve been thinking about nature and the feelings I get while being in it. I’ve been trying to capture these peaceful, quiet moments. Aside from a few years I spent in the South when I was a child, I grew up mostly in cities, and I had forgotten what being surrounded by nature feels like. Over time, I grew to not be scared in nature. If it wasn't for participating in residencies like Skowhegan and Guild Hall, I don’t think I would have come back to nature. In this work, you see the park by my old apartment, where I lived for about nine years. I would just take breaks from painting to go watch the sunset.

MG: So that's goodbye to your previous home.

AN: Yes. It turned out I couldn't stay in that area.

MG Does the almost abstract combination of red and blue have any special meaning to you?

AN: It reminds me of the sunset. Once I heard this song about a sunset that went like, ‘your purples and reds are making me blue.”That phrase always stuck with me. As I was painting this work, I was thinking how the purples and reds of the sunset can sometimes give you this feeling of nostalgia. I was listening to Neil deGrasse Tyson referring to how we evolved from something that once lived in the ocean, saying that we like looking at the ocean because it reminds us of where we've come from. Maybe that's why we get these nostalgic feelings looking at oceans and nature in the broader sense.

MG: The strength of your art is that it appeals to universal feelings and situations, such as being stuck in your life, longing for change, or saying goodbye to people and places. What about the portrait of the girl, I Knew You When I Had A Dream (But That Was Seven Summers Ago)(2022)?

AN: That's someone I knew when I just got out of grad school. I had all these aspirations of becoming an artist, and she had her own dreams, and we would stay up talking about who we wanted to become. For this painting, I was thinking about how even though time goes by so fast and relationships can change or fall apart, sometimes that still doesn’t take away from what it once was.

MG: Was it difficult to achieve this thick dense glitter impasto that forms her hair?

AN: It was a learning process. Before, I was getting the painting flat and tapping the glitter in. For some reason, I saw a video on sand paintings, where they used such a technique, and I thought that was how I should do the glitter, but it didn’t work at all. Over time, I started to paint it on. It drips and slides down in a certain way, because it's heavy, and I had to learn how to use it. Each year, I get more comfortable and knowledgeable on how to apply it.

MG: You made several drawings recently, all of them portraits. They have a similar formal approach: the face and the body are elaborately drawn using different colors, while the hair and the brows are left white like negative space.

AN: I've always drawn in the sketchbook using a graphite pencil, eraser, and sometimes charcoal, but I never really liked it. I would only do it to make a sketch, and at a certain point I stopped drawing entirely. When I was preparing for a talk at a school and was going through old images, I found a drawing that I made right after high school. I used conte, charcoal and a white pastel. It reminded me a lot of my paintings, and I also remembered having a lot of fun making it. I worked to incorporate the things I like about my paintings into my drawings, without feeling the necessity to draw everything if I didn't feel it needed to be drawn. This is the first year I've returned to drawing.

MG: Is there something that people misunderstand in your work? Is there something that you think people get wrong when looking at your work?

AN: I don't know what they think. I'm not defining meaning for anybody. When people look at my work, they bring their whole lives with them, and they may get something out of the work that I didn't even realize was in it right away. There was one painting I did [One day I’ll feel it too (Seeking Shelter (2017)] of a little kid stepping on one of the seekers. He had on Jordans. A school principal came to my studio and saw the painting, and mentioned a little kid, and someone who tried to take his shoes. He was asking me whether I raised that issue intentionally, but I didn't even see that at first! I grew up in a similar environment, where people were taking sneakers. It never happened to me, but I remember being worried it would when I was in elementary school, mostly because my family was concerned about it. So I can't disagree with what the man saw, because that was there in the painting–it’s something I was familiar with, and it came out in the work.

MG: Do you paint a lot? Are you spending long days in your studio?

AN When I was painting in my apartment, I didn't really keep track of it. I just did it all the time. I don't know if I'm painting for long days, but I do it every day, even if it's only for a few hours. These days, while preparing for the show, I’m an early riser. I get to the studio around 6 a.m., and I usually stay until the job’s done.

MG: Do you need a lot of time to make a painting?

AN: This upcoming show has five paintings, and I’ve been working on these for at least half a year. The painting is done in layers: I do the first part in acrylic; then I let that dry; then I lay it flat; thenIi put on a layer and let that dry again; and I repeat that process. Once I get to the oil paint part, it's pretty quick, but it usually takes about three or four months for one painting. I try to work on three or so paintings at once.

MG: You don't have any assistants, I assume.

AN: No.I actually like each step of the painting process.

MG: What do you hope to achieve through your art?

AN: I had this audiobook on the history of philosophy that started off with Aristotle’s question: what is a good life? That’s what I’m interested in: what does it mean to be a good person? There are some questions you can't answer until you're done. In the book, there is this story about the Minotaur, Ariadne and Theseus, and it talks about the string leading him out the labyrinth. Maybe the string represents understanding that helps you through the maze of life. Those are just the things I've always been curious about. What does it mean if I do this? Am I a good son? Why did that happen?

MG: Your painting is an excellent tool to analyze human relationships and morality.

AN: Exactly. If I have a question, then usually it ends up in a painting at some point.

MG: Then by being involved in the process of painting and thinking, you create something that maybe can help other people understand something.

AN: I think when you're more specific, somehow you reach more people than when you try to be vague. There's something about the specificity. It's like you listen to a song, and you may have not been through that exact thing that person's singing about, but they're so specific about what happened, and you feel that. The other day, I heard this comedian, who said that a good country song makes you reminiscent of times you've never had. I thought that was funny, because it's true. The colors, the image, the title, those little seekers–hopefully all those details come together to make you feel something and to allow you to develop your own connection to the painting.