Walton Ford

Published: April, 2018, ZOO MAGAZINE SPRING

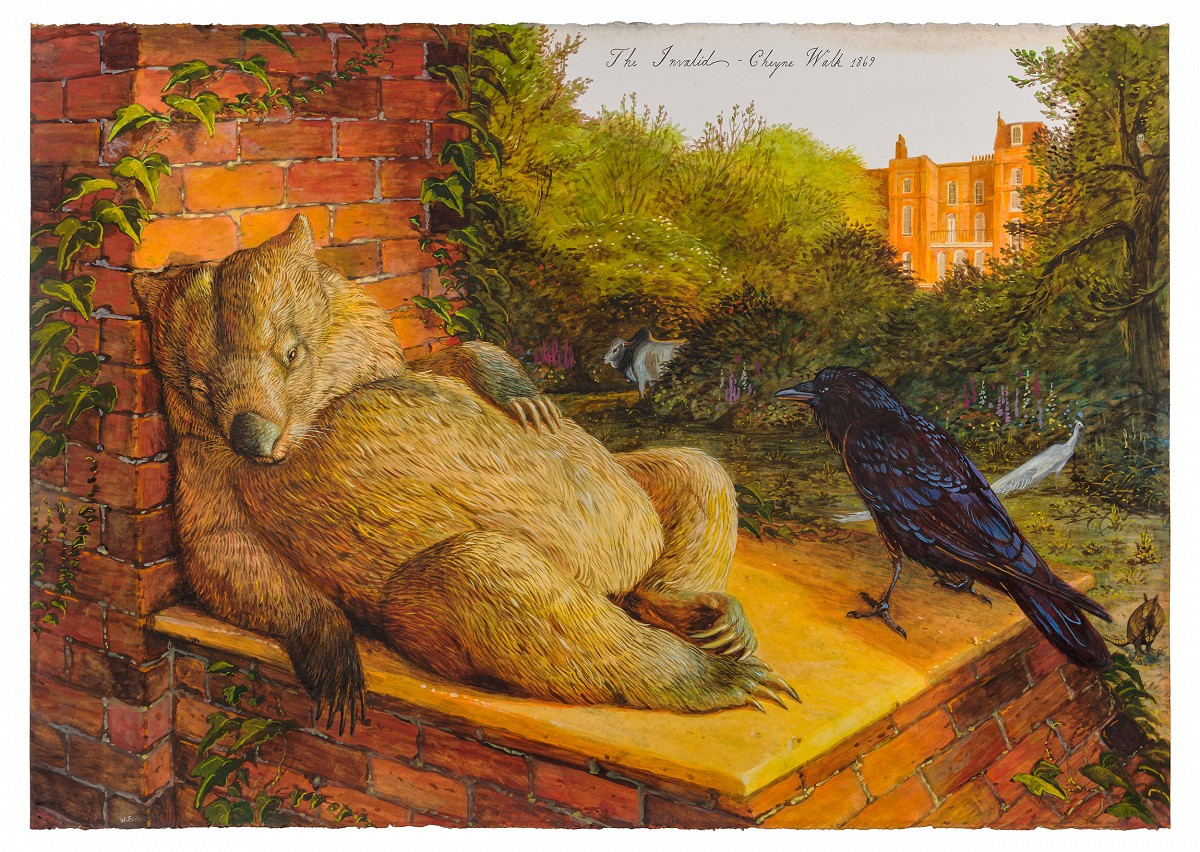

Marta Gnyp: I recently saw your beautiful work that has a sad, dying wombat playing the main role. Why a wombat?

Walton Ford: I do a lot of reading to get inspiration for my work. I have realized over the years that what I am most interested in are things you can probably classify as a cultural history of animals – particularly wild animals – and their interaction with human beings. Domestic animals have a sort of partnership with us that is mutual and that has developed in an evolutionary sense: dogs came to our camps, picked up scraps, and then they started to actually enjoy our company. The same can be said for almost every domestic animal. But we can’t make every animal domestic. We can tame individual animals, but we can´t domesticate entire species, like a tiger. Every tiger cub is born wild, wanting to get away from people.

MG: So, you are interested in how these wild animals have interacted with humans throughout history, and what this teaches us humans about ourselves.

WF: Exactly. I research and find strange stories. One of them was that of Gabriel Rosetti, the Pre-Raphaelite painter who lived in Cheyne Walk in London. He kept an extensive menagerie, but was a drug-addicted lunatic artist – in a very bohemian and contemporary way – like a crazy rock star of his era. He was not capable of understanding the responsibility of taking care of animals, but he was obsessed with wombats, and as soon as he could get one he got one. This wombat came and lived with this crazy bohemian community in Cheyne Walk and, of course, didn´t last long until he died. I found his correspondence about the death of this wombat. Rosetti did a self-portrait of himself weeping over the wombat and wrote a poem about his death. He called the wombat an invalid when it was sick and so “the Invalid” became the title of my painting. I gave to the wombat a particularly pre-Raphaelite treatment, including his pose and dramatic death on a piece of architectural scenery.

MG: You can see the wombat thinking “why did it happen to me?”

WF Sometimes I paint from the animal´s point of view, and sometimes from the human’s. In this case, I combined the two. I wanted to make palpable the suffering of the wombat, so that you could feel how unfortunate it is to be trapped by a group of 19th century opium-addicted, self-absorbed artists. At the same time, you can also feel the romantic spin that somebody like Rosetti would put on it.

MG: How did you become interested in themes about wild animals versus humans?

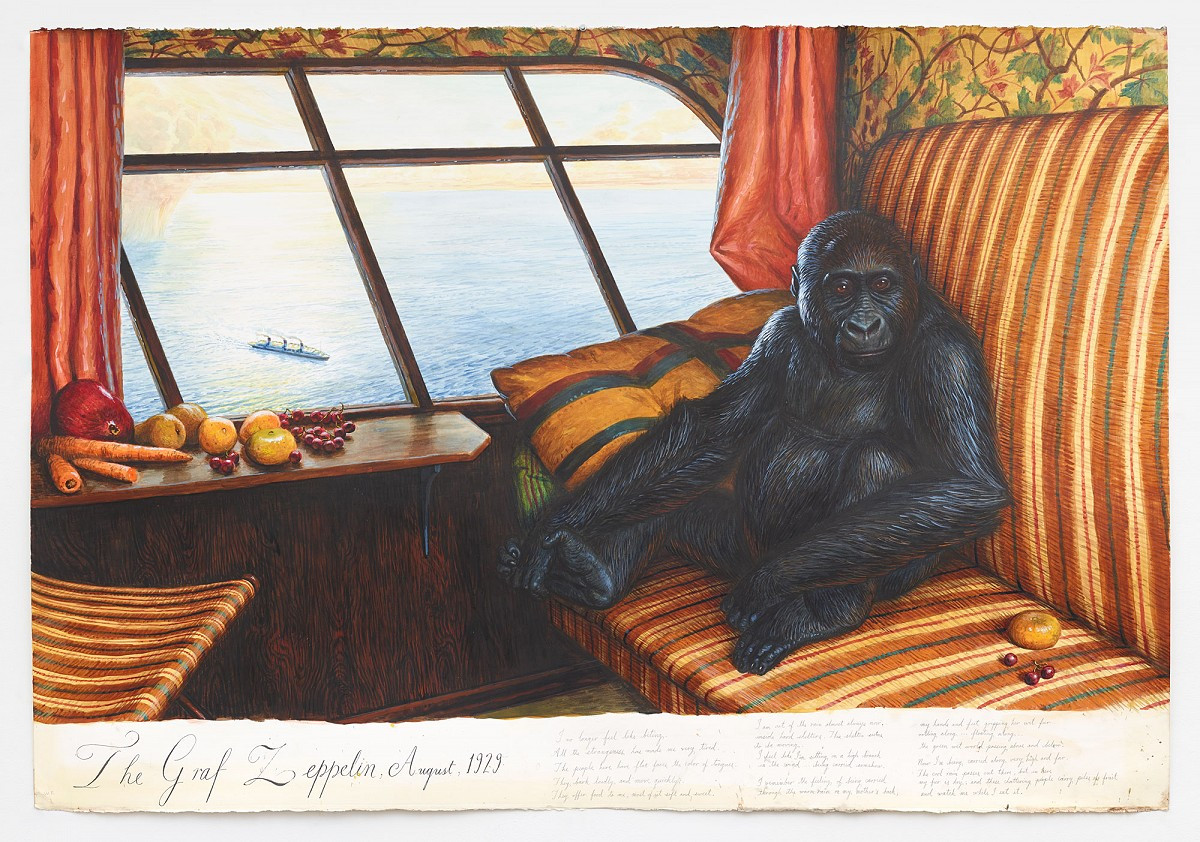

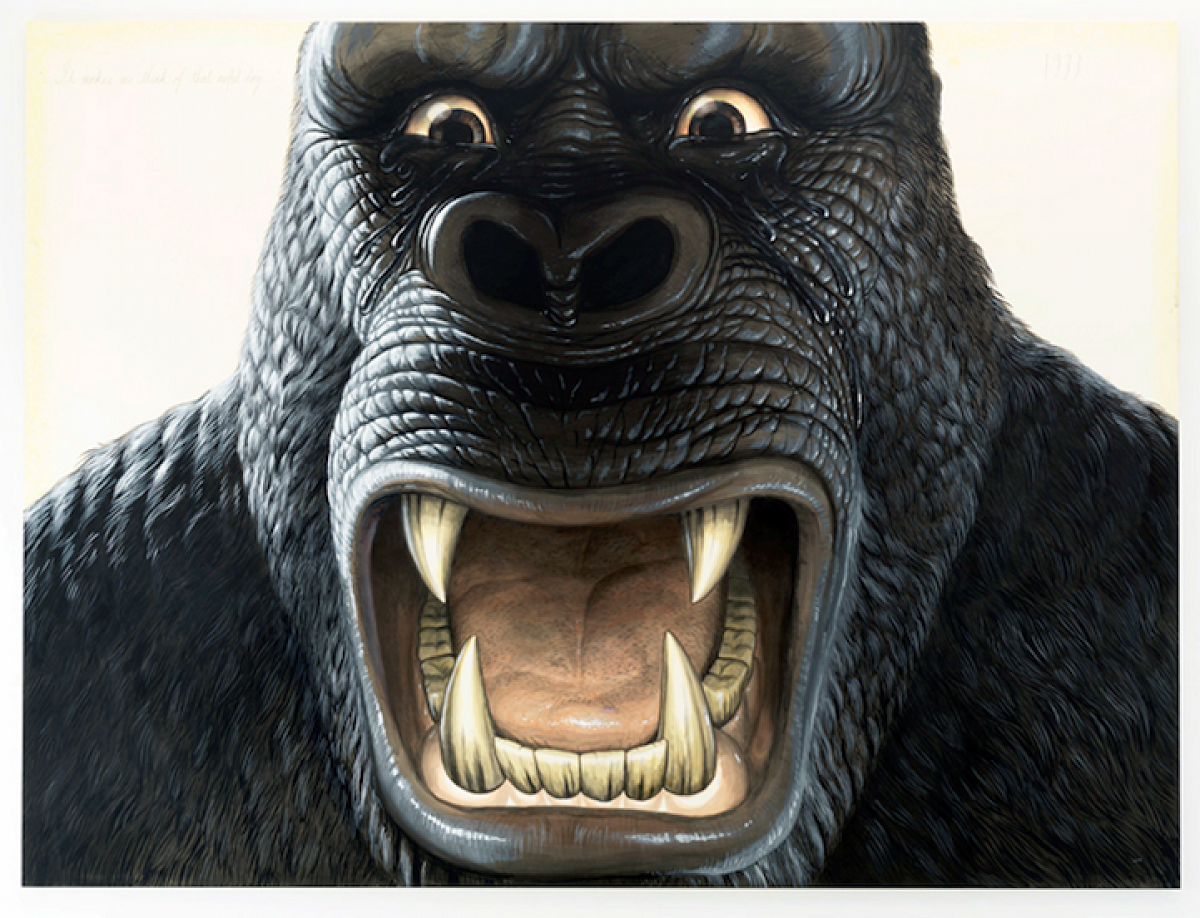

WF: I am a child of American suburbs. I would fantasize about the wilderness and I would watch films like King Kong, projecting myself into the story. My personal fantasy world that I built up in my head had to do with being in wild places.

MG: Why did you have this strong urge to escape into this fantasy wilderness?

WF: Mostly, I would climb a tree to get away from my father who was a bit of a bully. This tree was the only wilderness that I could find in the suburban setting. When you are on top of a very large, old tree, nobody can find you. The birds would fly by, and you could sit there for hours. When I started this work, these childhood memories resonated in a personal way.

MG: How did you start? Did you have a clear concept for your work?

WF: No. I made fake 19th century natural history paintings and I didn´t think they would matter to anybody. I slowly came into this project that now resonates outside of my own personal experience.

MG: Do you think that one condition for good art is that it must come from a profound personal experience?

WF: I believe that if you try to make issue-based art, it can become very preachy and insufferable. When you are trying to be didactic or be self-important about your message, it usually restricts your ability to reach people. I am lucky that this work came from a very personal place, and whether it was interesting to the rest of the world was irrelevant to me.

MG: In the meantime, our relationship to the nature has become a big issue.

WF: Yeah, look at what we are doing to the planet and all the animals that we share it with. It does become interesting to explore our relationships with these animals throughout history.

MG: Another very interesting aspect of your work is its narrative. I read that you wanted to be a film maker, so the idea of storytelling has probably always been of interest to you. If we look at what happened in the art world in the last twenty years, heavy conceptual thinking has given way to narratives. Is this one of the reasons why your art has become so interesting to the public?

WF: I guess the first time I noticed it was during my exhibition at the Hamburger Bahnhof.

MG: I saw this show – it was beautiful.

WF: Thank you. When Udo Kittelmann (the Curator and Director) put it together, he was deliberately making a statement. My show was scheduled before a big Bruce Nauman exhibition. Udo said that Bruce Nauman was always trying to get everyone pissed off with his work, but we have reached a point where Nauman has become acceptable – almost classical. There was no dispute. So, Udo put up my work because he knew it would upset people since it wasn´t going to fit into the official art discourse. He told me recently that every day, someone comes up – he likes to exaggerate, so it is probably every six months, but nevertheless – to argue with him over that show. They would say that it was illustrative, that it looked like a natural history museum, that it is not contemporary.

MG: How do you react to such comments? You have probably often been told that what you make is illustration and not art.

WF: I don’t pretend that my ego is so big that I don´t care. Every artist cares, so you come up with a response. I think that a huge part of the history of art is illustration. The entire Renaissance is basically an illustration of Bible stories being retold again and again. Here is an illustration of Adam and Eve, the life of Christ, the life of Mary – it goes on and on and on. You look at Goya’s works, which were illustrations of current events, and you think it is engaged and political – we accept it. The idea that it is wrong to make narrative stories that are, in some form, illustrations is a brand new construct that we can question. Why is it a bad thing to be called an illustrator?

MG: A very big part of the history of art is illustration and decoration, although art history doesn’t necessarily like this idea. Your art follows a different path that goes back to other sources.

WF: My generation was stuck. Robert Ryman, who is a great artist, said, “If we are going to make an honest painting, it’s got to be about paint. How do you make a painting about paint? You can remove the colours so you have only the white paint. You can focus on what kind of white it is – if I used this white out of this tube it is slightly warmer, this white from this tube is colder.” These were my teachers.

MG: So your generation had to liberate itself from the modernistic thinking about the purity of the medium.

WF: If I were an artist working in the 1950s and 1960s, I would have probably ended up in the same place. It would totally make sense. You keep on looking for the answers to the basic questions of your time, and you end up with this result. Like in an evolution, it has to happen – somebody´s going to paint that white painting. If you go into to Robert Ryman’s show, it starts to mess with your head because you see the differences between these two white paintings. Suddenly, your eyes start working in a different way – you are really attuned to your senses and it is a great experience.

MG: But the idea of pure modernist painting has been quite limiting.

WF: It is an intellectual exercise. I didn´t come to my work by going against it. In a funny way, I love the creative process in all of its manifestations. You have John Cage who says, “I am not making music, but I am using sound. I am just going to find the beauty in the sound.” I really believe that if you can follow someone like Robert Ryman or John Cage to the end of their thinking and take it seriously, you do get a result – it’s a sharpening of the senses.

MG: How did you justify that this attitude wouldn’t work for you?

WF: I’ve always been interested in the biological processes of evolution. I learned about the 19th century models of evolution that were progressive – the idea was that every animal is evolving into an improved version of itself and that everything is changing to become more intelligent and more human. But this is not what evolution is like at all! Evolution is like this crazy tree that grows in all directions, finding every atom for life without any hierarchy. There isn’t something that works better – you are simply finding paths for survival. Our history is like that too.

MG: No progress and no hierarchies for you.

WF: Young people today know this too. If you see a musical playlist by a person in their twenties, it is going to have Billie Holiday, some contemporary rap and classical music. It is all over the place because they don´t see a hierarchy. When I was young, at my art school people would say, “Punk is cool, disco sucks” or “Forget arena rock – we are not listening to Led Zeppelin anymore, we are listening to the Sex Pistols”. You had to make a decision. We don´t make a decision now.

MG: Is it not confusing that everything can exist next to each other?

WF: You start to see that the world is full of interesting things. I think that this is progress, actually. But we are taught in our history to reject the past in favour of the present.

MG: The art world is one of the last solid bastions that tries to keep this hierarchy and old order alive.

WF: Yes! I find that museums are the most timid in this respect because they have invested the most in a story of progress. I studied in Italy in my senior year. I was an American kid who had never been out of the country before. I went to Italy and I saw the frescoes, the churches, and the Giottos. I realized that the idea of progressive art history was wrong – it implies that if Medieval artists knew how to use perspective, they would have done it. The point is that they didn´t have any interest in it. If you were making a Medieval painting, you were trying to create a painting about invisible spiritual enlightenment. You were not interested in creating a natural world, because you had to grasp at an inner world of spirituality. I thought that they were perfectly capable of doing whatever they wanted to do, it’s just that this is what they chose to do. I never bought into the idea that we don’t have choice or agency because we are stuck in this progress story and are not allowed to be tangential.

MG: The progress story has had its own agenda. Perspective was a great instrument to give art the status of science and make it more prestigious. Speaking about museums and their agenda, how have institutions treated you? I read that your first museum show was at the Brooklyn Museum in 2006, which was relatively late. I was wondering if anything has changed between 2006 and 2018?

WF: That it is true, but I do feel that things have changed a lot. The Brooklyn Museum is a very good example. Anne Pasternak, the current Director, is very open and creates a dialogue. She even sent a letter to artists, including me, asking for feedback. She is very good at interacting with artists, rather than just doing all the fundraising and keep the narrative going. It’s probably best to look at this from institution to institution to be fair. I have felt a lot more acceptance lately.

MG: Do you have an explanation for this?

WF: Sometimes I think that if you just stick around and don´t give up, they will get used to you. When I was in college, somebody like Cher, who was a joke in the Disco era, started to be acceptable. Now she is like Mount Rushmore – nobody would say anything about her. You don´t go away. Maybe that´s all it is.

MG: Are museums buying your work?

WF: I have some museums that want my work, but it is still hard to find somebody that will purchase my work and then donate it. If I give the work away, then you run the risk of having it go into storage. Nobody really values something they are just given. I just think it takes time. Right now, I can´t complain because everything seems to be going well. People are paying attention, looking at the work and liking it. I pretty much have what I could hope for as an artist: an audience and the ability to get up and go to the studio instead of having some job that I hate.

MG: Let’s go back to the beginning of your career. You finished at the art academy in the beginning of the 80s and came to New York. The 80s and 90s must have been very difficult times for a young artist in NYC.

WF: I had nothing going on in the art world back then. I was in the studio every day, but I worked in manual labor jobs as a carpenter and metal worker. I helped build museum exhibits, doing whatever job I could get, and lived in the cheap neighborhoods in Williamsburg. Back then in 1983, no artists were there. Greenpoint was a Polish neighborhood with a lot of abandoned buildings. In the Italian part of Williamsburg where I lived, there was a very tightly knit community with cappuccino and pizza parlours, and a few low-level mafia living there. I could just keep on working because I kept my head low.

MG: If we speak about the beginning of the 80s, this was the time of the Picture generation, of Neo-expressionism and also of Basquiat. Who was most appealing to you?

WF: I wasn´t aware of anybody as much I was aware of Basquiat, who was exactly my age. Picture generation people like Cindy Sherman were a bit older, well established, and already a big deal.

MG: Did you speak with anybody about your art?

WF: Nobody was interested in what I was doing, in East Village or anywhere else. Still, something encouraging would happen every year. I got the Guggenheim Fellowship, and one year Bill Arning (now Curator at the MIT) or Marcia Tucker (now Curator at New Museum) would come to the studio and say that I had amazing work. I could live off that for one year. Marcia put me in a group show, as she understood that my works were going in a really weird direction. She was kind of a genius, but couldn’t really do anything. I had a day job and I used to babysit her kid, who is now all grown up.

MG: What about your artist peers?

WF: I was an artists’ artist perhaps. Other artists thought I was up to something interesting. Anyways, I knew I was no good at anything else.

MG: What were you good at? That thing that we referred to as illustration and nature?

WF: I did a lot of paintings about my childhood memories in my twenties, which was a kind of sorting through trauma, but then I saw David Lynch’s Blue Velvet and thought, “Oh shit, he did it better than I ever could, so I will leave that alone.” Later on, I became interested in the nature and history of the 19th century. Both sides of my family were very old American families from the South. They came over in the 18th century to one of the first settlements. My father´s family settled in Tennessee. Before it became a city, Tennessee was a plantation owned by my family. My mother´s family settled in North Georgia way back in the 1750s. My parents were liberal and artistic southerners, so we came North to get away from the conservative thinking that they grew up with and didn´t like. I was raised in this progressive household, but with southern people carrying a history of plantation and slave-owning in their past.

MG: Any guilty feelings about that in the family?

WF: I didn’t do anything. I wasn’t even raised that way. My father would cry every time he saw To Kill a Mockingbird, although you could open old family memoirs and scrap books with confederate money in it – really amazing. I could go to the South and talk to relatives who were bigots that were my flesh and blood. This put even more distance between me and them. I understood that best when I went to Germany – a German that was born in 1960 isn’t a Nazi. But I do have to think about it, and I explore it in my paintings.

MG: There is a lot of cruelty and violence in your paintings.

WF: For sure. If you have a family who lived in America since the 18th century and was prominent, there is no question that their history was extremely violent – that there were natives that had to be killed off, tons of wildlife that had to be slaughtered, forests that had to be cleared, slaves that were brought over to do all the work. You can’t avoid the horrors of an old family in America. You can’t pretend that your own flesh and blood wasn’t a part of the violence, so I was interested in exploring that. Although my family was very enlightened, I was raised to have pride in the fact that we were here before anyone else, whatever that’s supposed to mean. It still made them a little better than everyone else.

MG: It sounds like a very complex issue, which might explain the complexity of narratives in your work.

WF: I didn´t want a packed answer – I didn’t want to let myself off the hook. I used to hear from bigoted relatives that we were a family that was kind to slaves. I don’t even want to hear that shit.

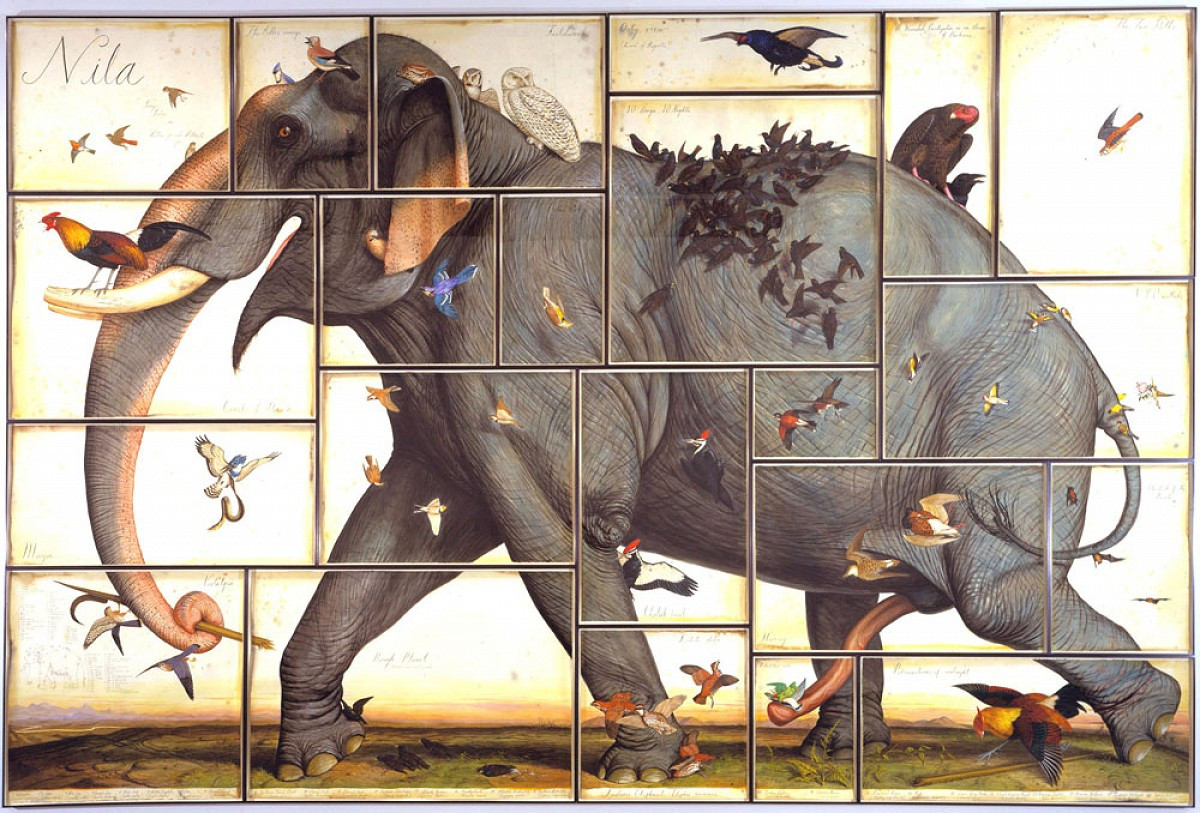

MG: So your interest in history and nature are both very personal. Then you came across this famous book by Audubon called The Birds of America, which gave you a methodology for how to pursue your interests?

WF: It wasn’t just him that I devoured, but every natural history artist that I could get my hands on. I read books about prehistoric history, and would know about artists who were famous for drawing dinosaurs. I became a nerd got science museum art and textbook art. I would know artists who illustrated guide books and field guide books, such as Peterson, who was this really important bird guide artist. As a child, I didn´t know where it was going to lead, but I knew that this was what I was interested in from a very early age. I thought maybe I would make guidebooks and illustrate children´s books about natural history. Or maybe I would work in a museum or in a national park. I was trying to imagine a future for myself that allowed me to make paintings about this world. I think I would be delighted if I could see the life that I put together for myself.

MG: What about the medium you have chosen? You make big works on paper and use watercolours, which is not easy. There are not many artists who have a career as bit as yours from using mainly paper.

WF: The first time I tried to make my own natural history art as a child, I paraphrased artists. I copied Audubon and Edward Lear, who wrote Pussycat, and did beautiful illustrations of birds and things. Generally, natural history artists used watercolours, ink and gouache, and they worked on paper, partly because they made drawings and notes about animals, discoveries and encounters on expeditions in their journals in the field. They had to use watercolours because oils take a long time to dry, and they are very hard to transport. If you have a little paper journal, you can just make a sketch of a bird you just shot, put watercolour on it, close it and put it in a waterproof sack, and carry it to the next place.

MG: You used watercolours on paper because they have traditionally been the medium for natural history artists.

WF: Exactly. These expedition watercolours were a big part of my childhood. The language of natural history art starts with Dürer´s work The Rabbit in the Albertina Museum, which is a watercolour gouache ink on paper. It hasn’t changed because it is a very good way to immediately make a study of living or dead things.

MG: You learned that language quite early.

WF: Then I went to art school and I forgot all about it. I painted, I made films, I acted – I did all these various things to figure out different ways of telling stories. Eventually, I came back to what I was doing as a child, just picking up watercolours and making these fake nature studies. Once I started doing that, I decided that I wanted to amplify the scale and take something that would have been in a small journal, but make it a life-sized animal. The first one I did was a tiger – it was 10 ft by 5 ft and very elaborate. I knew that I could do it from a technical standpoint, because it is very close to fresco work, which I studied when I was in Italy. You have to make these preparatory drawings and you have to be very careful, and when you finally paint you have to know what you are going to do. I thought that if you can paint a fresco with life-sized figures, I can paint this watercolour. No big deal technically compared to what they did.

MG: Frescoes were painted very quickly.

WF: You could find the seams where they would plaster as much as they could paint in one day, so you don’t paint the entire thing overnight. I do the same thing when I’m painting my watercolours. I just give myself what I can handle. Each day I do more, but I don’t need to finish the whole thing at once. When you finally see the finished product, it’s 9 by 12 ft, and you can’t figure out how I did it. That’s how I felt when I looked at these frescoes for the first time.

MG: Do you paint by yourself, without assistants?

WF: No assistants at all – I don´t like that.

MG: Why not?

WF: The best part of the art-making job is making the art. I totally admire workshop artists like Damien Hirst or Jeff Koons, but to me they are CEOs of large business corporations that make luxury objects at a very high level. For me, this is the worst part of the job. I never set out to run Mercedes Benz – I’m not interested in high-end manufacturing. I want to sit there like the craftsman and make the beautiful thing with my own hands and my own skills. I have assistants, but their work is to make sure that I’m going to make the flight or make Skype work.

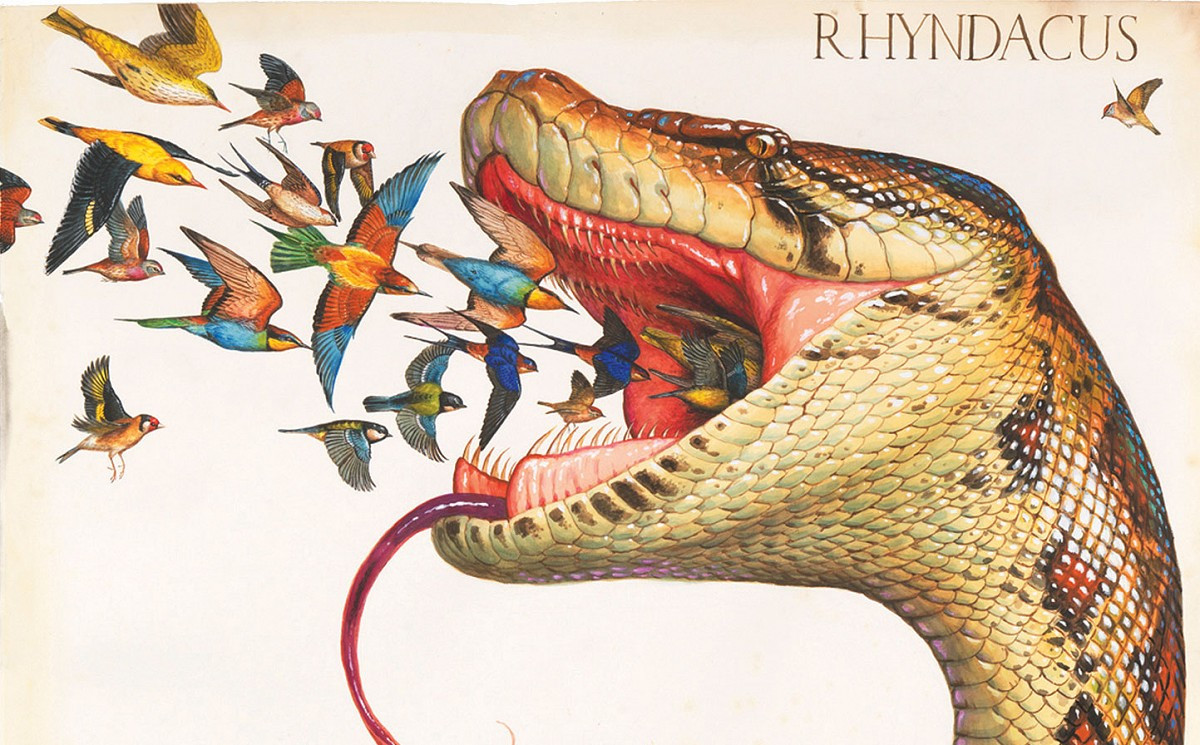

RHYNDACUS (FRAGMENT)

MG: What do you think about the idea of the artist today? You mentioned the tyoe of the CEO of a luxury brand corporation. At the same time, the idea of the artist as a bohemian, revolutionary or as avant-garde have become old fashioned. So, what is so special about an artist today?

WF: When I was in my twenties, it seemed very clear. If you were in New York in the 80s, you knew that what was happening there was very special and was not understood by the general population at all. I could go to a concert for $5 and see the Talking Heads play. I would see these outfits and these drag queens – I would go to the Pyramid Club. I’m lucky to be alive, because a lot of people from that time are dead. We weren’t taking care of ourselves in the 80s in downtown New York or in Brooklyn. I felt like we were all shamans that understood something that other people didn’t.

MG: How did it manifest itself?

WF: I got clothes from the Salvation Army, like a suit that was 30 years old – it was weird, really out of sync with the rest. if I watched MTV, I saw guys in leather jackets with big shoulders who looked ridiculous to me – like Michael Jackson outfits. We were more like strangers in paradise, walking around in these sort of fedoras and old suits, and we felt like we were ahead of the curve. We would be looking like the guy from Joy Division. I would hitch hike and I had my head shaved so people would ask me whether I was in the Marines, but I would reply with, “No I´m in an art school”.

MG: You were one of the avant-garde trendsetters.

WF: Except that my art was all fucked up. I was cool when I went to the club, but people didn’t quite understand why I was making these old fashioned pictures. Regardless, I felt like I was in the right place at the right time. I was hearing music that no one was going to hear for years to come. We would always know about things beforehand. This idea of the artist seems over now, and I don´t understand where is it going. Today an artist feels very lucky if he gets a corporate gig like a shoot for a fashion magazine. In the 80s, there was a purposeful rejection of such actions.

MG: Were you against corporate structures?

WF: I don’t want to go back in time, but yeah, the feeling was “fuck the man and the corporate world”. When an artist started selling his paintings, he was immediately suspect and immediately had to buy all the drugs, invite everybody to dinner, spend all their money on other people and not live in a better place. You might have lived in a bigger place, but it had to be a shithole on purpose. It was important not to pretend that you were like some kind of Wall Street guy.

MG: The Wall Street guy was the ultimate horror?

WF: Exactly.

MG: Today, your works are expensive and you are making money.

WF: Today, my feeling is that artists should get paid well. Why should it just be movie stars, sports figures, industrialists or people in the startups making money? It’s cool if an artist gets paid for what he does and so I’m all for that. I think that the art-making impulse is the best one we’ve got. The second best is our altruistic behavior. Those are the two things that make us different from bacteria or some horrible virus – we’re destroying everything we touch. If I go to the Met today, I look through all this unbelievable stuff they have and I feel good about being a human being. I don’t feel bad about being a successful artist because if you’re successful, you have a chance for your work to be cared for because it is somewhat expensive.

MG: What do you think about the new generation of artists?

WF: My girlfriend is younger than me. She’s a dancer and she recently brought me to some dance performances that were really cool. There is still really interesting stuff – young choreographers and musicians experimenting. The scene of young artists doesn’t feel so different, but I don’t think that they feel that something is going on in a palpable way.

MG: Don’t you think that the younger generation now is more moralistic?

WF: Well, the moralistic thing is like a pendulum swinging. The biggest difference between my generation and theirs is their lack of a sense of community. When I came to New York, there was the East Village gallery scene – everybody was in a band and would go home, paint and then go to the same bars and the same restaurants. The rent was cheap, the food was cheap and shitty, and the drugs were expensive. Everybody was doing the same thing, listening to the same music and reading the same books. There was a lot of uniformity in that, but it also created a sense of community. Right now, as it gets more and more expensive to live in the inner cities, the beautiful neighborhoods that were available to young artists are no longer affordable, so they live in different places. There´s not one neighborhood that they all gravitate towards. It is not their fault, it’s a real estate issue – It´s a greed thing.

MG: What are you working on right now?

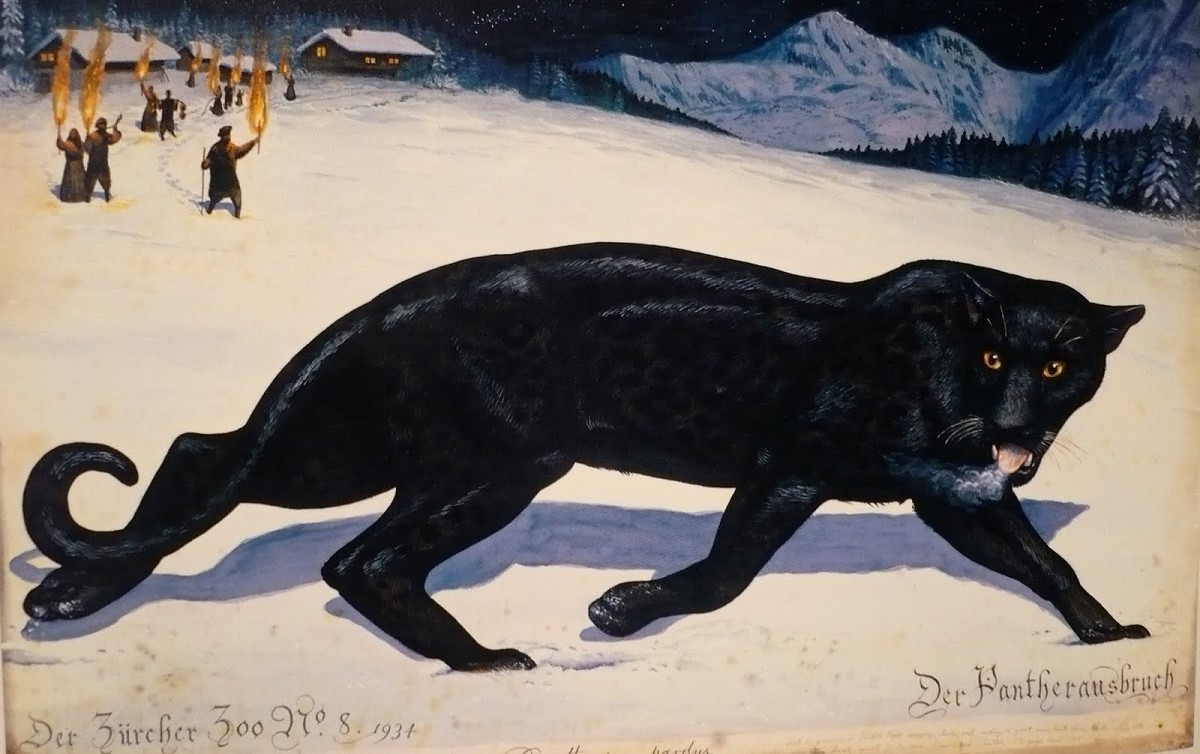

WF: I have a small exhibit in St. Moritz with Vito Schnabel, who took over the beautiful old gallery of Bruno Bischofsberger. I’m making a show about a subject that I explored many times, but I’m doing it again because it’s perfect for this gallery. There was a female black panther who escaped from the Zurich Zoo in the winter of 1933. For ten weeks, she was in the Swiss countryside and nobody could find her. They never found the tracks. They had clairvoyants try to find her, and they asked the police to chase her. Then, ten weeks later, some peasant found her under a barn, shot her and ate her. He treated it like he shot a deer – he butchered her and cooked her up. So, this story is everything I´m looking for. It was from this book called Wild Animals in Captivity, a kind of zookeepers’ manual. Since I found the story, I’ve been making paintings about her constantly. Sometimes, I have her floating above the snow because she didn’t leave any tracks, and I make her into a sort of magical creature. I have a painting of her with fire in the snow in the evening when she´s walking away on the smoke, and the fire is the one she was cooked on. I have a lot of ideas about her all the time. She’s a sort of dream animal.